A Land Worth Fighting For: The Palestinian Struggle As Seen in The Series The Land and I by Nabil Anani - Yasmine Nowroozi

February 16th, 2025

Margaret Mitchell, author of Gone with the Wind, famously writes: “The land is the only thing in the world worth working for, worth fighting for, worth dying for, because it’s the only thing that lasts”. Today, her statement echoes the struggles and sorrows of the Palestinian people. Since the early twentieth century, the Palestinian landscape has borne witness to the erasure of its people’s heritage and livelihood. What was once a land vast in greenery is now one that is grey, barred, and stained with the blood of its people. However, one Palestinian artist dares to challenge this rhetoric and paint the land from grey to something that is both bold and vibrant. Contemporary artist Nabil Anani represents his people’s resilience and inalienable connection to the land through his collection, The Land and I. His use of folkloric motifs within his landscape highlights humanity’s connection to nature while also disturbing the longstanding Zionist attempts at ascribing a Jewish identity to the Palestinian landscape. The dreamlike character behind his pieces speaks of the Palestinians' hope that their land will be free. That being said, Nabil Anani’s The Land and I urges the viewer to understand the Palestinian environment and its people through a new lens– courageous, resilient, and rich in colour.

Nature Versus Man

Nabil Anani’s The Land and I opposes Zionist discourse regarding the question of land ownership by representing the Palestinian people’s indissoluble connection to the land. Anani imbues the landscapes of his collection with various elements of Palestinian heritage; from images of orange trees and olive groves to folkloric motifs and colors of the Palestinian flag, Anani’s artwork is undeniably and unapologetically Palestinian (Talass, “Palestinian Artist Nabil Is Redefining Aarb Impressionism”). Anani further cements his Palestinian pride and identity into his canvases using Middle-Eastern spices, such as Zaatar, turmeric, and sumac, as painting mediums (Talass, “Palestinian Artist Nabil Is Redefining Aarb Impressionism”). These spices, integral to various Middle-Eastern dishes, further emphasize the inseverable ties between people, culture, and land as these spices come from the very grounds the people live on and tend to. Moreover, Anani’s use of Zaatar is a powerful act of resilience against a longstanding law created by Ariel Sharon in 1977, which declares Zataar as a protected plant (Eghbariah 106). This law forbids the cultivation, usage, and trading of the plant (Eghbariah 106). Any individual found guilty of any of the preceding offences could face conviction (Eghbariah 106). In doing so, Anani is reclaiming the Palestinian people’s right to the land.

Additionally, in 1934, the Jewish National Fund (JNF) commissioned a series of maps in which Palestine was refashioned into a Jewish settlement; therefore, erases the land’s ties to its Arab heritage but also divulges the Zionists’ political agenda (Fields 274). Through this campaign, the JNF proclaims: “This land is ours” (Fields 274). Simultaneously, the JNF’s new maps act as a visual aid of the Zionist narrative, which aims at ascribing the Palestinian landscape to a Jewish character (Fields 274). In doing so, the Zionists declare the Palestinian people as unnatural “others”; intruders who have no claim to the land and who are unlawfully trespassing (Fields 274). The Zionists’ vision of a land free of Palestinians will eventually come to fruition in 1948 with the War of Independence, otherwise known as the Naqba (Fields 276). The aftermath of the war led to the creation of a new legal process in which Israeli residents could acquire abandoned Palestinian properties (Field 276). The Zionists’ absorption of Palestinian properties continued well into the 1960s with their preying on the land of Palestinian villages within the new state (Fields 276). The Zionists borrow from Article 78 of the Ottoman Land Law of 1858, which previously stipulated that Palestinians had a right to the land they worked on so long as the Ottomans could tax it, to enforce their plans (Fields 276). However, Israeli lawyers modify this law by stating that all “land to be without ownership if cultivation failed to cover 50% of the land surface” (Fields 276). Although the Palestinian people are working the land, they no longer have any claim to it. The modification of the Ottoman Law thus facilitates the realization of a Jewish landscape within Palestine with the creation of over 700 Jewish settlements (Fields 276). Since 1967, Israel continues to enforce a settlement program within occupied Palestine (Fields 277).

Consequently, Anani’s collection The Land and I challenges Zionist rhetoric by presenting the onlooker with a landscape devoid of checkpoints, cement barriers, or settlements (“The Land and I”, Zawyeh Gallery). By using spices as a painting medium, Anani is, therefore, “grounding his art in the materiality of the land itself”(“The Land and I”, Zawyeh Gallery) and restoring the Palestinian landscape to its rightful owners, safe from the oppressor's pressurizing hands. His representation of Palestine’s natural landscape reinforces its rich history and relation to the Palestinian people and culture— the barrier between humanity and nature no longer exists and, instead, the two become a single unit (“The Land and I”, Zawyeh Gallery). The unification of humanity and nature not only strengthens the idea that land is a living being but that it also bears witness to the Palestinian people's struggle (“The Land and I”, Zawyeh Gallery). Together, the two share a past, a present, and future (“The Land and I”, Zawyeh Gallery). Anani’s portrayal of nature reflects his philosophy of life, that land is the foundation for everything (Talass, “Palestinian Artist Nabil Is Redefining Aarb Impressionism”). Anani expresses the preceding through the inclusion of a mother nature-like figure caressing a tree within his painting, The Gem (fig. 1). The figure’s flowing hair melts seamlessly into the landscape as she stands tall at the centre of the canvas. Her caressing of the tree hints that she both cares for and carries the burden of the state of nature. The figure’s tatreez, a traditional Palestinian embroidery technique, of two women and five children reiterates the idea that nature and women are bearers of life. As does a mother, nature passes its legacy onto its creations. The personification of the natural world; therefore; emphasizes the spiritual and physical relationship between humanity and nature. When describing this painting, Anani shares: “the figure of a woman appears within the landscape as an allegory for Palestine– the mother, the source of nourishment and shelter for her people” (Turki, “Palestinian artist Nabil Anani’s evocative ‘The Land and I’ on display in London”). Hence, the message Anani aims to convey through his collection The Land and I expresses humanity’s relatedness to nature. However, do the bold colours and lack of settlement presence in various pieces of The Land and I suggest a false reality of the Palestinian landscape?

Through Imagination Comes Resilience

In his collection, The Land and I, Anani expresses his thirst for freedom, resilience, and pride in the land through his reimagination and idealization of the Palestinian landscape. Though the use of bold colors and abstract shapes may seem odd to the viewer, Anani claims these elements are imperative to understanding the message he aims to convey– one that speaks of the unwavering sense of strength and honor of the Palestinian people. In a recent interview with Architectural Digest Middle East, Anani shares the reason behind his stylistic choices:

Therefore, Anani’s portrayal of the Palestinian landscape speaks of the soul’s connection to nature. His use of abstract shapes calls to the dreamlike state one enters when reminiscing about one's home. Though the shapes become somewhat intelligible in one’s reverie, the love and connection we share for our home remains. Anani expresses the preceding through bold colors as they are synonymous with the feelings of happiness one feels when nostalgic.

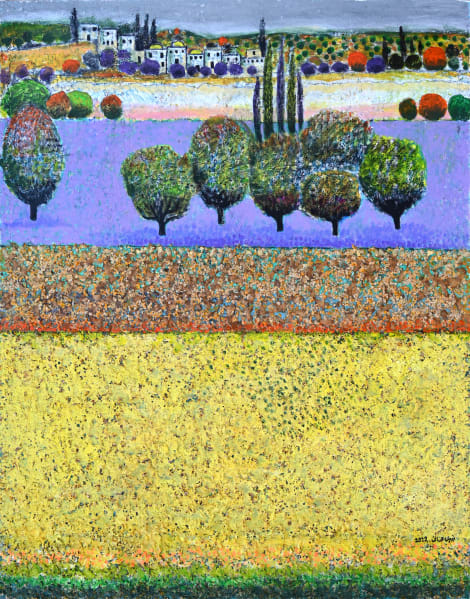

However, Anani includes some elements of reality in his pieces. Anani’s use of horizon line perspective in his pieces (fig. 2, fig. 3, fig. 4) reminds the viewer of the reality of the landscape. Anani draws all of the idyllic landscapes in The Land and I at a distance, thus reminding the viewer that this version of Palestine is out of their reach (Talass, “Palestinian Artist Nabil Is Redefining Aarb Impressionism”). The Zionist settlements hinder the Palestinian people’s access to their land, and they are left grasping at memories of a land that once was. Hence, Anani’s re-imagination of the Palestinian landscape speaks of the dream that his people share of a land that is free.

Nabil Anani’s Collection The Land and I is a testimony of the Palestinian people's struggle, resilience, and undying love for their land. Through Anani’s Inclusion of folkloric motifs, he reminds the viewer of the Palestinian land’s long-standing Arab heritage. His use of bold colors and abstract shapes speak of the nostalgia and hope many Palestinians share when reminiscing about their land. Although Anani’s pieces are a re-imagination of the reality of the Palestinian landscape, his application of horizon perspective reminds the viewer of the current impossibility of his representation due to the ongoing Israeli occupation of Palestine.

“The Land and I”. Zawyeh Gallery, https://zawyeh.net/nabil-anani-the-land-and-i/

Talaas, Rawaa. “Palestinian Artist Nabil Anani Is Redefining Arab Impressionism”. Architectural Digest Middle East, https://www.admiddleeast.com/story/palestinian-artist-nabil-anani-is-redefining-arab-impressionism

Turki, Tamara. “Palestinian artist Nabil Anani’s evocative ‘The Land and I’ on display in London”. Arab News, https://www.arabnews.com/node/2281816/lifestyle

Nature Versus Man

Nabil Anani’s The Land and I opposes Zionist discourse regarding the question of land ownership by representing the Palestinian people’s indissoluble connection to the land. Anani imbues the landscapes of his collection with various elements of Palestinian heritage; from images of orange trees and olive groves to folkloric motifs and colors of the Palestinian flag, Anani’s artwork is undeniably and unapologetically Palestinian (Talass, “Palestinian Artist Nabil Is Redefining Aarb Impressionism”). Anani further cements his Palestinian pride and identity into his canvases using Middle-Eastern spices, such as Zaatar, turmeric, and sumac, as painting mediums (Talass, “Palestinian Artist Nabil Is Redefining Aarb Impressionism”). These spices, integral to various Middle-Eastern dishes, further emphasize the inseverable ties between people, culture, and land as these spices come from the very grounds the people live on and tend to. Moreover, Anani’s use of Zaatar is a powerful act of resilience against a longstanding law created by Ariel Sharon in 1977, which declares Zataar as a protected plant (Eghbariah 106). This law forbids the cultivation, usage, and trading of the plant (Eghbariah 106). Any individual found guilty of any of the preceding offences could face conviction (Eghbariah 106). In doing so, Anani is reclaiming the Palestinian people’s right to the land. Additionally, in 1934, the Jewish National Fund (JNF) commissioned a series of maps in which Palestine was refashioned into a Jewish settlement; therefore, erases the land’s ties to its Arab heritage but also divulges the Zionists’ political agenda (Fields 274). Through this campaign, the JNF proclaims: “This land is ours” (Fields 274). Simultaneously, the JNF’s new maps act as a visual aid of the Zionist narrative, which aims at ascribing the Palestinian landscape to a Jewish character (Fields 274). In doing so, the Zionists declare the Palestinian people as unnatural “others”; intruders who have no claim to the land and who are unlawfully trespassing (Fields 274). The Zionists’ vision of a land free of Palestinians will eventually come to fruition in 1948 with the War of Independence, otherwise known as the Naqba (Fields 276). The aftermath of the war led to the creation of a new legal process in which Israeli residents could acquire abandoned Palestinian properties (Field 276). The Zionists’ absorption of Palestinian properties continued well into the 1960s with their preying on the land of Palestinian villages within the new state (Fields 276). The Zionists borrow from Article 78 of the Ottoman Land Law of 1858, which previously stipulated that Palestinians had a right to the land they worked on so long as the Ottomans could tax it, to enforce their plans (Fields 276). However, Israeli lawyers modify this law by stating that all “land to be without ownership if cultivation failed to cover 50% of the land surface” (Fields 276). Although the Palestinian people are working the land, they no longer have any claim to it. The modification of the Ottoman Law thus facilitates the realization of a Jewish landscape within Palestine with the creation of over 700 Jewish settlements (Fields 276). Since 1967, Israel continues to enforce a settlement program within occupied Palestine (Fields 277).

Consequently, Anani’s collection The Land and I challenges Zionist rhetoric by presenting the onlooker with a landscape devoid of checkpoints, cement barriers, or settlements (“The Land and I”, Zawyeh Gallery). By using spices as a painting medium, Anani is, therefore, “grounding his art in the materiality of the land itself”(“The Land and I”, Zawyeh Gallery) and restoring the Palestinian landscape to its rightful owners, safe from the oppressor's pressurizing hands. His representation of Palestine’s natural landscape reinforces its rich history and relation to the Palestinian people and culture— the barrier between humanity and nature no longer exists and, instead, the two become a single unit (“The Land and I”, Zawyeh Gallery). The unification of humanity and nature not only strengthens the idea that land is a living being but that it also bears witness to the Palestinian people's struggle (“The Land and I”, Zawyeh Gallery). Together, the two share a past, a present, and future (“The Land and I”, Zawyeh Gallery). Anani’s portrayal of nature reflects his philosophy of life, that land is the foundation for everything (Talass, “Palestinian Artist Nabil Is Redefining Aarb Impressionism”). Anani expresses the preceding through the inclusion of a mother nature-like figure caressing a tree within his painting, The Gem (fig. 1). The figure’s flowing hair melts seamlessly into the landscape as she stands tall at the centre of the canvas. Her caressing of the tree hints that she both cares for and carries the burden of the state of nature. The figure’s tatreez, a traditional Palestinian embroidery technique, of two women and five children reiterates the idea that nature and women are bearers of life. As does a mother, nature passes its legacy onto its creations. The personification of the natural world; therefore; emphasizes the spiritual and physical relationship between humanity and nature. When describing this painting, Anani shares: “the figure of a woman appears within the landscape as an allegory for Palestine– the mother, the source of nourishment and shelter for her people” (Turki, “Palestinian artist Nabil Anani’s evocative ‘The Land and I’ on display in London”). Hence, the message Anani aims to convey through his collection The Land and I expresses humanity’s relatedness to nature. However, do the bold colours and lack of settlement presence in various pieces of The Land and I suggest a false reality of the Palestinian landscape?

Through Imagination Comes Resilience

In his collection, The Land and I, Anani expresses his thirst for freedom, resilience, and pride in the land through his reimagination and idealization of the Palestinian landscape. Though the use of bold colors and abstract shapes may seem odd to the viewer, Anani claims these elements are imperative to understanding the message he aims to convey– one that speaks of the unwavering sense of strength and honor of the Palestinian people. In a recent interview with Architectural Digest Middle East, Anani shares the reason behind his stylistic choices: I wasn’t painting scenery exactly how I saw it, but I was capturing the soul of the view. I am also implementing my own style of painting and feelings into the work. It’s good to dream a little when making art, just to get out of a certain moody atmosphere. If I were to paint a village scene, I make it abstract, simplifying the components. It becomes like a dream and that takes over making anything realistic (Talass, “Palestinian Artist Nabil Is Redefining Aarb Impressionism”).

Therefore, Anani’s portrayal of the Palestinian landscape speaks of the soul’s connection to nature. His use of abstract shapes calls to the dreamlike state one enters when reminiscing about one's home. Though the shapes become somewhat intelligible in one’s reverie, the love and connection we share for our home remains. Anani expresses the preceding through bold colors as they are synonymous with the feelings of happiness one feels when nostalgic.

However, Anani includes some elements of reality in his pieces. Anani’s use of horizon line perspective in his pieces (fig. 2, fig. 3, fig. 4) reminds the viewer of the reality of the landscape. Anani draws all of the idyllic landscapes in The Land and I at a distance, thus reminding the viewer that this version of Palestine is out of their reach (Talass, “Palestinian Artist Nabil Is Redefining Aarb Impressionism”). The Zionist settlements hinder the Palestinian people’s access to their land, and they are left grasping at memories of a land that once was. Hence, Anani’s re-imagination of the Palestinian landscape speaks of the dream that his people share of a land that is free.

Nabil Anani’s Collection The Land and I is a testimony of the Palestinian people's struggle, resilience, and undying love for their land. Through Anani’s Inclusion of folkloric motifs, he reminds the viewer of the Palestinian land’s long-standing Arab heritage. His use of bold colors and abstract shapes speak of the nostalgia and hope many Palestinians share when reminiscing about their land. Although Anani’s pieces are a re-imagination of the reality of the Palestinian landscape, his application of horizon perspective reminds the viewer of the current impossibility of his representation due to the ongoing Israeli occupation of Palestine.

Fig. 1 The Gem by Nabil Anani, 2022.

Fig. 2 The Land and I (1), Nabil Anani, 2021

Fig. 3 The Land and I (2), Nabil Anani, 2021

Fig. 4 The Land and I (3), Nabil Anani, 2022

Works Cited

Fields, Gary. “This Land is Ours: Collective violence, property law, and imagining the geography”. Journal of Cultural Geography. Vol. 29, No. 3 (2012), pp. 274-276. Fig. 2 The Land and I (1), Nabil Anani, 2021

Fig. 3 The Land and I (2), Nabil Anani, 2021

Fig. 4 The Land and I (3), Nabil Anani, 2022

Works Cited

“The Land and I”. Zawyeh Gallery, https://zawyeh.net/nabil-anani-the-land-and-i/

Talaas, Rawaa. “Palestinian Artist Nabil Anani Is Redefining Arab Impressionism”. Architectural Digest Middle East, https://www.admiddleeast.com/story/palestinian-artist-nabil-anani-is-redefining-arab-impressionism

Turki, Tamara. “Palestinian artist Nabil Anani’s evocative ‘The Land and I’ on display in London”. Arab News, https://www.arabnews.com/node/2281816/lifestyle