A Psychoanalytic Exploration of the Work of Louise Bourgeois: Trauma, Therapy and Catharsis – Charlotte Pierrel

JANUARY 28, 2021

Throughout her seventy-year long career, Louise Bourgeois (1911-2010) used art as a mode of processing and translating psychological distress and intense pain. Revered and regarded as one of the major contemporary figures of the twentieth century, Louise Bourgeois was a French-American avant-garde artist, whose work explored personal suffering and whose importance as an artist is rooted in her exploration of identity through psychoanalysis. Best known for her installations and colossal spider sculptures, Bourgeois was driven to express her personal history of childhood trauma and rejection of experienced misogyny as an act of catharsis by dealing with profound human emotions of abandonment, rage, fear, loneliness and sexuality. In a 2007 e-mail exchange with the Los Angeles Times, she shared that her art was “a form of psychoanalysis” which gave her access to the depths of her unconsciousness and a means of exorcising pain which constituted her “guarantee of sanity” (fig. 1).1 According to art historians Michael Hatt and Charlotte Klonk, a psychoanalytical approach to Louise Bourgeois’ work demands a ‘psychic biography’ of the artist, or an exploration of the artist’s childhood experiences and possible traumas.2

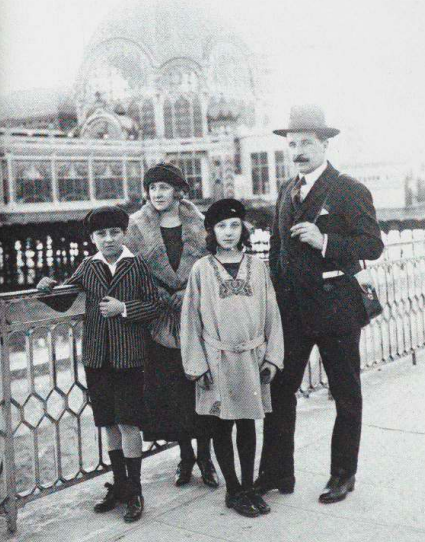

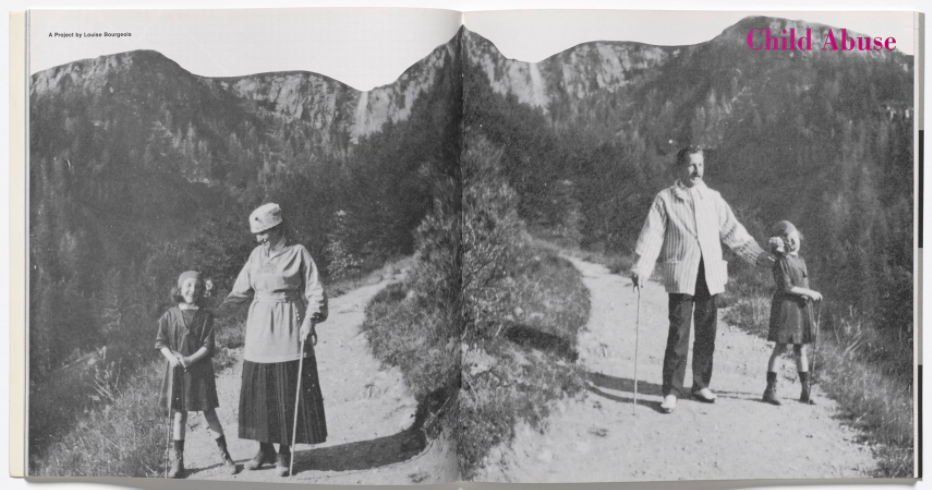

Born in Paris and raised in Choisy-le-Roi, Bourgeois’ father was a domineering patriarch who would hold court at dinner and humiliate his young daughter in front of guests with taunting and lewd jokes. The artist remarked, “My father had a cruel sense of humour and I could not answer it… I could not make myself feel understood.”3 A serial philanderer, her father’s ten-year affair with the artist’s young English tutor Sadie whilst her mother was often bedridden having contracted Spanish Flu was, as Bourgeois explained, a “double betrayal” which destroyed the family idyll and her trust towards her adored governess (fig. 1).4 In a 1982 illustrated book Child Abuse: A Project by Louise Bourgeois (1982) (fig. 2), she would later explain: “There are rules of the game. You cannot have people breaking them right and left. In a family, a minimum of conformity is expected.”5 When Louise’s mother died from tuberculosis in 1932, her father’s mockery of her grief, ensuing depression, and sense of abandonment provoked an attempted suicide. In her adult life, Bourgeois would experience severe depressive and psychotic episodes, agoraphobia, insomnia and anxiety attacks as a result of her father’s damaging actions and behaviours. Art thus provided her a psychological outlet that let her feel heard and have her feelings acknowledged. In her own words, Bourgeois states it enabled her to have “the last word” against her father. English film director Nigel Finch’s BBC film Louise Bourgeois: No Trespassing (1994) shows the artist’s painful excavation of childhood memories required in her cathartic artistic process. In her studio, Bourgeois explains that twenty-five years later, she still feels resentment against her father, and only when she is able to throw plates on the ground and stomp on the scattered broken pieces can she “start to exist.”6

Louise Bourgeois was undeniably the eternal, rebellious runaway girl who refused to be silenced by her father’s cruel mocking and remarks. Despite his protestations, she pursued an art education and began a lifelong journey of creation as therapy. She married art historian Robert Goldwater, and in 1938 settled in New York and raised three sons. “I left France because I freed myself or escaped from home. I was a runaway girl. I was running away from a family situation that was very disturbing.”7 It was only when her father died in 1951 that Bourgeois began psychoanalytic therapy with Dr. Henry Lowenfeld, a radical Freudian analyst. Although Bourgeois tackled themes of the unconscious in her work, and recognized herself as a hysteric, she ultimately rejected Freudian and Lacan theories. In a 1962 essay called “Freud’s Toys,” she would even explicitly ridicule Freud’s theories and declare “The truth is that Freud did nothing for artists, or for the artist’s problem, the artist’s torment.”8 Having only gained public recognition for her first MOMA retrospective in 1982, the artist was seventy years old when her childhood experiences were publicly revealed for the first time in her photo essay, Child Abuse (1982). This illustrated book would reveal her traumatic childhood story, with photos, sketches, and notes detailing her experiences of the events, a unique and sensational window into the artist’s psyche which contributed greatly to art history and psychoanalytic academics’ understanding of her work.9

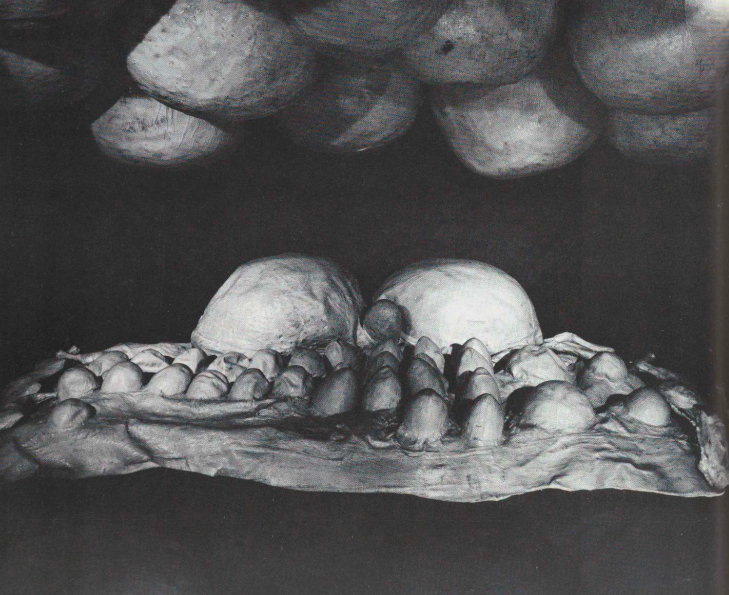

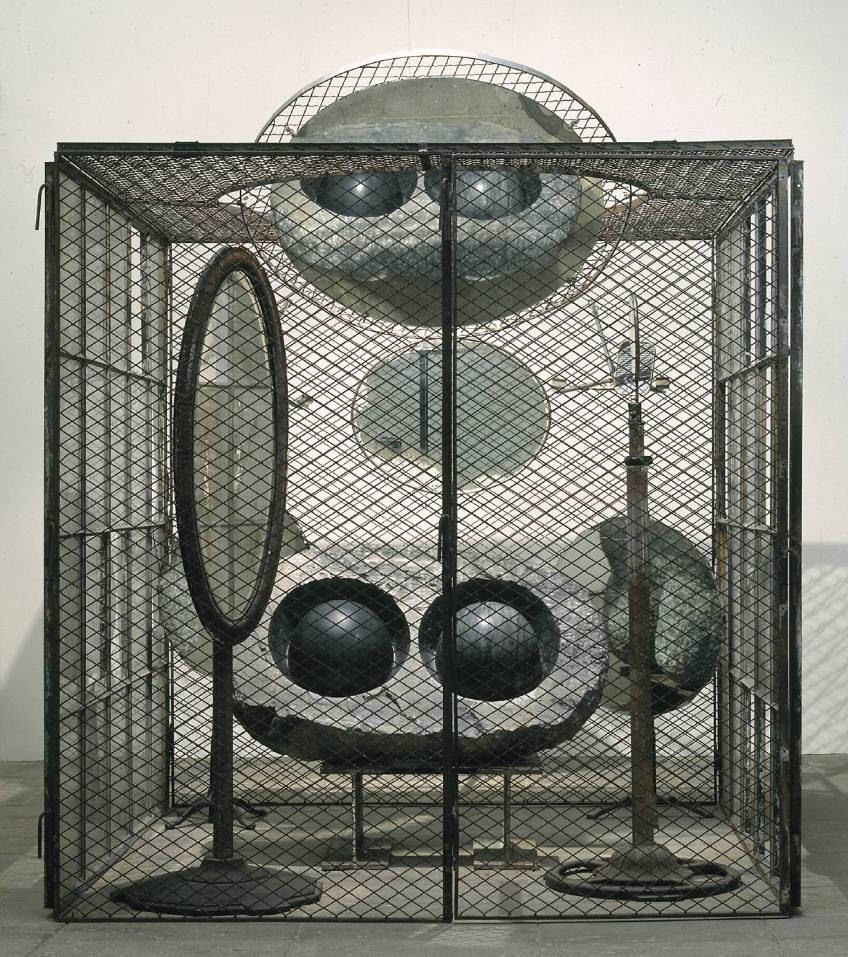

Louise Bourgeois would perpetually revisit painful memories and fantasies exploring the themes of home and family. Embodying the artist’s trauma from her father’s infidelity and domestic aggression, The Destruction of the Father (1974) (fig. 3), produced at age sixty-three, is a testament to the artist’s continuous efforts to cope with her father’s tyranny and reclaim a degree of agency. In a cave-like structure, bulbous forms resembling body parts, made of plaster and latex, are centered around a dining table – the designated place for the unfolding drama. Dramatized by a nightmarish red light, viewers become witness to what The London List identified as “the aftermath of a crime.”10 Bourgeois was very explicit in noting that the installation’s inspiration arose from a childhood fantasy of dismembering and consuming her dictatorial father at the family dinner table, with journalist and writer Rachel Cooke defining it as a “visceral statement of intent.”11 In a taped 1981 interview, Bourgeois explained that The Destruction of the Father was “an act of exasperation and justice… I wanted to relive and make other people relive that experience.”12

Reversing the power dynamics and reclaiming agency of her life and subjectivity, Bourgeois’ fantasized rebellion against her father’s authority indexes her ongoing refusal to continually be subjugated and tormented by him. As the artist’s first self-enclosed installation, The Destruction of the Father explores the potential of architecture and its possibilities in placing the artist as a spectator in a theatre observing the family drama, providing her enough distance to ‘take pleasure’ in looking. In Nichel Flinch’s film Louise Bourgeois: No Trespassing, Bourgeois explains her frustration at her inability to respond to her father’s cruel mocking, but it is only when she is able to destroy materials that she retaliates and finally obtains recognition of her trauma.

Art historians and scholars have attempted to read the work’s fantasy of aggression towards the father according to Freudian psychoanalysis, most notably through psychoanalyst Jacques Lacan’s theory of ‘patricidal fantasy’ – an unconscious act of (sexual) pleasure which has been repressed from childhood and needs to be perpetually re-lived by the artist. Exploring the work’s ambiguous tensions between pleasure and aggression, Lacan’s interpretations read the dinner table as a bed and the bulbous forms as sexual, characterizing the artist’s act of violence as an unconscious oedipal struggle for an erotic bond with her father as a result of his abuse. However deeply engaged Bourgeois with psychoanalysis, she later went on to fundamentally distance herself from Freudian theories – we should therefore embrace her work as “breaking free of these strictures.”13 Freudian readings undermine the artist’s possible unconscious desire and need for the mother – a fantasy of returning to the mother’s womb, a time and space which predates her trauma. Bourgeois’ unconscious desire could have perhaps been reuniting with her mother, visually reflected in the breast-like forms and more generally in the intimate interior reminiscent of a womb. Louise Bourgeois’ best-known and seminal work Maman (1999) (fig. 4) represents the culmination of the artist’s exploration of the maternal through the theme of the arachnid, which the artist first contemplated in a charcoal drawing in 1947.14 A symbol of nurturing love, protective presence and of mending, Bourgeois referred to these works as “[a]n ode to my mother.” Alluding to her mother’s relentless strength facing both illness and betrayal, the sculpture Maman is a testament to the artist’s admiration of her mother’s role as a female protector and repairer. Mender of painful emotions, the spider is a weaver and nurturer, speaking to the artist’s childhood recollections of her mother who was in charge of the family tapestry workshop and was her “best friend.” Perhaps Bourgeois admired and looked up to her mother precisely because “she could defend herself,” unlike herself who felt so incredibly powerless confronting the tyranny of her father.15 Inviting multiple readings and perspectives, it is far too limiting to read The Destruction of the Father from a single vantage point and previous readings solely based on the artist’s possible oedipal struggle exclude equally relevant interpretations.

One of the most significant influences on Louise Bourgeois from the mid-century was the work of Melanie Klein, the radical psychoanalyst known for her work on object relations theory in connection to child development. In this case, ‘object” is the embodiment of primal emotions such as fear, desire or envy. The Oedipal narratives of Freud were replaced with the object world of infantile drives directed to the mother and the death drive, and concerned theories about childhood aggression. Klein upheld that children split off parts of their personalities to cope with otherwise unmanageable, conflicting feelings. Bourgeois used representations of fragmented and dismembered bodies, referred to as ‘part objects’ to channel a journey into deep locked emotional trauma, a pre-verbal existential anxiety rooted in infancy. Nature Study (1986) is a small bronze sculpture of a hand intentionally likened to a tree root that holds a tiny naked woman. This work seems to come directly from Kleinian theory of complex emotional states revealed through ‘part objects.’ Klein believed the primary ‘part object’ to be the mother’s breast and certainly much of Bourgeois’ work uses this as a theme. In Fantastic Reality, American art historian Mignon Nixon maintains that above all else Bourgeois’ work is fundamentally Kleinian in that the creative process Bourgeois underwent – from attacking, to destroying and reconstructing – reflect life and death instincts in perpetual tension.16

Similar to Child Abuse, her extensive series Cells (1989–93) (fig. 7), produced at age seventy, offers psychological microcosms of the artist’s struggle in her exploration of the childhood home, memories and fantasies. These self-enclosed installations are unique architectural units which, according to Bourgeois, are homes housing fears. Built from cage-like materials, each cell is filled with a collection of salvaged objects found by the artist which echoes her childhood and to History of Art professor Alexander Potts have “obvious psychic resonances, which go beyond a vague sense of spatial interiority.”17 Both prisons of suffering and houses of safe haven, they combine memories of traumatic events, but also fantasies of an ideal home for the artist in order to reconstruct her past and have agency over it. Literary critic and theorist Mieke Bal describes Bourgeois as a ‘builder’ of these “houses of the mind.”18 In Cells, architectural imagery presents the home as both a refuge and a jail which can simultaneously protect and imprison us. Some, like Spider (1997), feature a hovering spider over the cage, at first threatening but symbolizing “the mother who mended and healed, comforted and protected” and which provided the child artist to “stand unbearable family tensions.”19

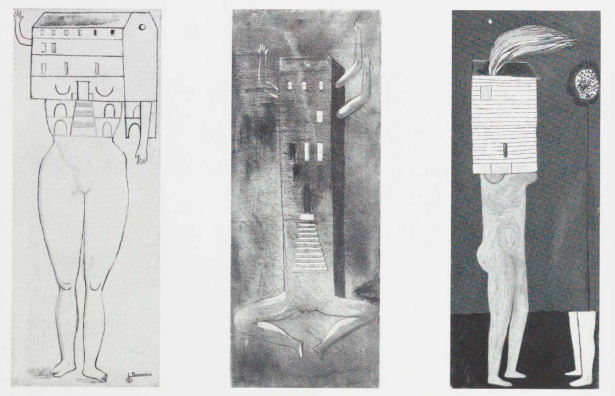

Bourgeois knew all too well the gender politics of her time. Femme Maison (1945-47) (fig. 5), explores the theme and issue of domesticity, dealing directly with the objectification and sexualization of women. In the United States, she felt incredibly home-sick and the political post-war climate of the time greatly impacted her work and mental state. In this series, the artist illustrates naked female figures whose heads have been replaced by houses, some of which are on fire, and whose arms desperately wave for help. By isolating the female body from the outside world, and placing the female head within the home, one cannot help but think the Femme Maison are trapped in a patriarchal society. Mignon Nixon reads these figures as “trapped by domestic travail and maternal devoir,” longing and “daydreaming of liberation.”20 Symbols of the home and of the private sphere, the work references the female condition in the 1940s, drawing attention to the gendered trap in which they have been cornered. Author and curator at MoMA, Deborah Wye, additionally reads the figures as ‘suffocated’ by architectural imagery of the home.21 Bourgeois claimed the presence of their hands indicates their attempt to “ call for help” – “erotic without knowing it,” the women are asking for anyone to “come and rescue [them] from eroticism.”22 Their exposed nudity further exemplifies the ways Bourgeois was concerned with the inherent male gaze, and the sexualization and objectification of women’s bodies.

Bourgeois’ latex sculpture Avenza (1968-1969) (fig. 6) pushes the sexualization of the female body further, featuring the artist proudly wearing a multi-breasted garment in the city streets of New York. According to British artist and professor Elizabeth Manchester, the bulges evoke “instincts and urges from pre-sexual, possibly even prenatal existence,” detaching itself from the sexualization of the male gaze. Bourgeois wrote that these rounded latex breast-like forms are not only anthropomorphic but are also “landscapes” because “our own body is a figuration that appears in mother earth,” highlighting the role of the male gaze in sexualizing body parts. Organic rather than sexual, these forms have regularly been referred to as ‘part-objects,’ referring back to psychoanalyst Melanie Klein’s theories on the development of young children. Here, yet again, Bourgeois explores questions regarding sexuality, desire and gender, and at the heart of it, the mother’s breast.23

Since a child Bourgeois was repeatedly made aware that her birth was somewhat of a disappointment given that her father, Louis, had wanted a son. She would recall her mother’s distress at the idea of having disappointed her husband with yet another daughter.24 In the documentary film Louise Bourgeois: The Spider, The Mistress and The Tangerine (2008), directed by Amei Wallach and Marion Cajori, Bourgeois re-enacts a childhood memory of her father peeling a party tangerine, a ritualistic “form of entertainment” aimed to humiliate his daughter at the family dinner table. Incising lines on the tangerine’s skin with a marker, the artist painfully peels back the shapes of the rind to reveal a silhouette with “big breasts,” and at the fruit’s core, a phallus. At seventy, her father’s “detestable” humor is still traumatic as she remembers her father hilariously exclaiming he regrets that his daughter is deprived of “such beauty,” the penis.25 In psychoanalytic literature, the castration complex developed by Freud was a theory of the unconscious anxiety in females to demonstrate that they have an adequate symbolic equivalent to the penis, which provokes a ‘penis envy.’ Bourgeois’ lifelong exploration of memories and persistent need to construct her own autobiography reveals the effects of her father’s violent remarks as a child, particularly those concerning her body and female figure. By replacing the female sex with an artificial penis – the tangerine’s core, Bourgeois was denied of her own femininity by her father who would have taught her that without a penis, the female sex is wounded, cut and incomplete.

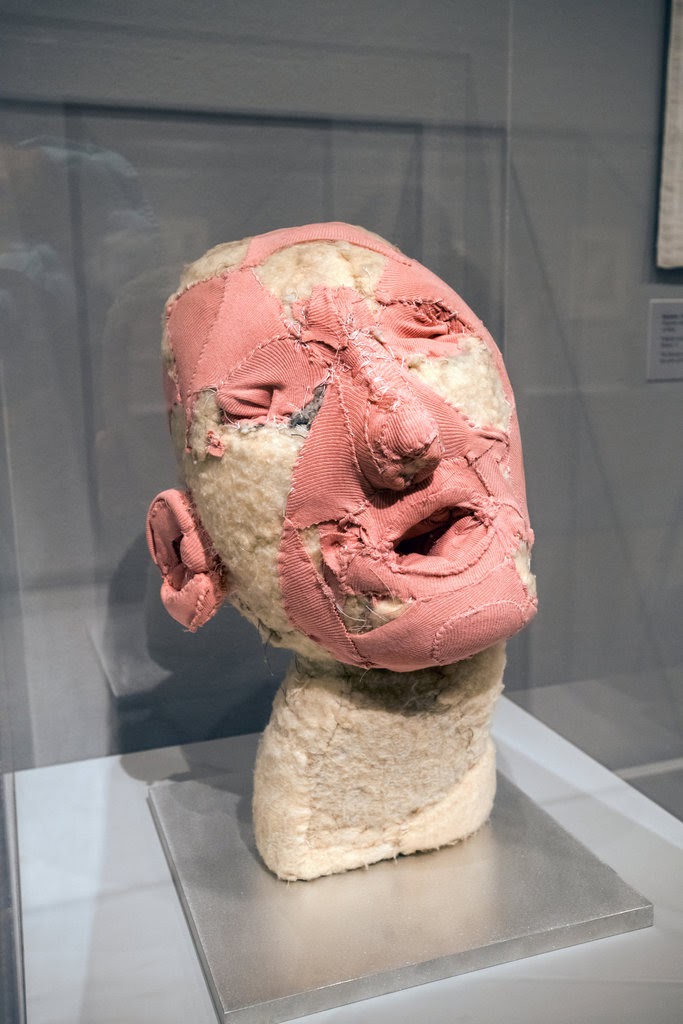

In an interview for the MoMA, explaining her sculpture Torso, Self-Portrait (1963-1964) (fig. 8), Bourgeois explained she experienced this part of her body “with a certain dissatisfaction and regret that one’s own body is not as beautiful as one would like it to be. It doesn’t seem to measure up to any standard of beauty.”26 These loathing self-views can be interpreted as body dysmorphic, expressing a painful corporeal dissatisfaction that feminists have viewed as a projection of the male gaze upon the female subject, something which the artist was overly exposed to by her father. These wounds are shown in her textile works, such as Arched Figure (1999) (fig. 9), and Untitled (1998) (fig. 10), where torsos have been mutilated, cut, gouged and hacked away. In a 1993 diary entry, Bourgeois had written that “Art comes from a need to express – an idea or a concept – cutting, mutilation, self-mutilation. Pruning, control. How to prove to yourself.”27 In these tortured fabric dolls, she advertises the disgust she felt for her body and self, and the subconscious belief that punishment is somehow deserved because of how her female gender was continuously mocked by her father. These fragments of her body, split apart and somehow put back together, enact the artist’s process of deconstructing and reconstructing, acting as catalysts for her psychological states.

According to Julia Kristeva in her book Powers of Horror: An Essay on Abjection (1980), abjection refers to the breakdown in the distinction between definitions of the ‘self’ and the ‘other.’ Abject bodies threaten liminality – their transgression of “boundaries of the body, of the self” destabilize the viewer’s sense of cleanliness and propriety, which according to feminist professor Kate Chedgzoy evoke “disgust or horror.” One can apply Julia Kristeva’s notion of the abject to Bourgeois’s artworks and acknowledge the artist’s exploration of her sufferance and struggles related to her body image, as well as the ways in which the female body has been fragmented and rendered ‘grotesque.’ Here, Bourgeois’ bodies threaten liminality and transgress bodily boundaries by their orifices, cuts and anatomical insides, which unsettle the presumed male viewer’s psyche and space, challenging preconceived notions of the ‘proper’ and ‘feminine.’ According to feminist scholar Kate Chedgzoy, an expert in politics of gender, sexuality and women’s cultural production, the female body is rendered abject by the misogynist and “technological gaze of patriarchal culture.” Bourgeois deconstructs gender discourses and reclaims her body as part of her subjectivity – an act of resistance against her father’s misogyny and other misogynistic male artists of her time, like Max Ernst, Hans Bellmer and André Breton. These men envisioned women in dehumanizing ways and treated the female body as an object of aggressive, erotic fantasies.

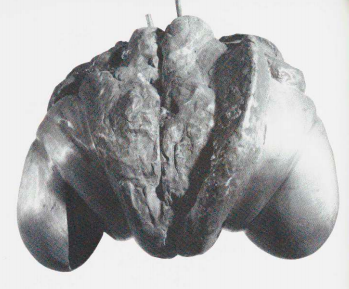

Bourgeois’ sculpture Janus Fleuri (1968) (fig. 11) is a testament to Bourgeois’ refusal to adhere to traditional gender norms. Exploring gender ambiguity, this biomorphic bronze sculpture fuses male and female anatomy in a symmetry of phalluses emerging from a female body, appearing to have blossomed, or fleuri. Janus Fleuri is a complex expression of elements, both threatening and protective – existing simultaneously in the male and the female organic forms. Neither distinguishably female nor male, the sculpture seems to be in an unpredictable state of metamorphosis. The work refers to the double-faced Roman god Janus, god of gates and doorways, beginnings and endings – while the doors of his temples would be closed in periods of peace, they would open in periods of war. Janus Fleuri clearly addresses polarities on so many levels. Acknowledged as supremely autobiographical, Bourgeois herself alluded to the push and pull between an impulse of “extreme violence” and the desire to retreat and. Janus Fleuri is a complex expression of contradictory elements which can both be threatening and protective and here, the artist uses male and female organic forms to express these polarities. We can argue that Bourgeois was really pushing the boundaries of feminist art even while the concept itself was in its infancy. It could be argued that, in blurring gender boundaries, Bourgeois avoids the threat of objectification provoked by the male gaze. According to art historian and cultural analyst Griselda Pollock, Bourgeois’ exploration of gender ambiguity is a “denunciation of phallocentric and patriarchal society.”28

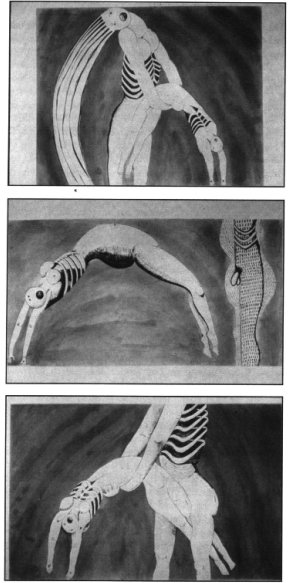

Bourgeois gave artistic voice to intrinsically female experiences like childbirth, menstruation, and oppression. Convinced she was unable to have children, Bourgeois adopted her first child. Having suffered postpartum depression upon the births of her own children, Bourgeois felt deeply overwhelmed by feelings of inadequacy, describing that she was, “ afraid of [her] family…afraid not to measure up.”29 In many of her artworks, she explores the birth experience – both her own and that of her children – as an event that reflects polarized maternal instincts, ambivalence, love and hate, gratitude and fear, and connection and repulsion. The maternal body is, according to Chedgzoy, the quintessential abject body. However, Bourgeois reclaims her experience of motherhood by breaking societal taboos and masculine subjectivities regarding maternity. In Triptych for the Red Room (1994) (fig. 12), the artist deconstructs the cultural myth that maternity transcends aggression. Examining Bourgeois’ complicated relationship to the maternal, feminist art historian Rosemary Betterton believes the artwork bears, “witness to the desires and losses, pleasures and pains of the older maternal body.” Betterton argues that Bourgeois’ late maternal works relating to birth and fertility, at eighty, speak to her desire to break down the ‘maternal ideal’ and cultural myths which later in life imply reconciliation and serenity. In Triptych for the Red Room, fifty years after the birth of her sons, Bourgeois produced a three-part print, representing two nude, rigid, and arching figures – seemingly a woman and a man taken by anxiety and hysteria. Their painful facial expressions, as well as their body language, suggests this very maternal ambivalence with the child. The rawness and vividness of the repulsion are evident in their yearn to escape one another through violence and torture. Their psychological pain affects their bodies, turning them into hysteric, contorted skeletons. Whether pain or ecstasy, the piece works to convey complex emotions associated with motherhood. The historically gendered concept of hysteria is important given that many psychoanalysts, like Freud, confirmed the scientific validity of the ‘female hysteric.’ In his book Studies on Hysteria (1865), Sigmund Freud, founder of psychoanalysis, argued neurosis began in the female uterus, through the conduction of individual studies of female hysterics – thereby gendering and medically diagnosing the concept of ‘female hysteria.’ Bourgeois came to understand hysteria was not an exclusively feminine phenomenon. Bourgeois not only breaks the taboo of maternity, but also takes a feminist approach to psychoanalysis, showing that hysteria can affect both men and women.

Bourgeois was undoubtedly a powerhouse of profound ambivalences and has been praised as a monumentally important artist for her relentless engagement with uncertainties about her pain, her gender, being a mother, and more fundamentally about being someone who could ever be worthy of love. In the peak of the circulation of both misogynistic Freudian psychoanalysis and second-wave feminism, Louise Bourgeois perpetually negotiated and reclaimed artistic and therapeutic space in which she could cope with her experiences of trauma. Over the course of her prolific seventy-year professional career, complete artistic energy was devoted to addressing and healing her childhood wounds, her artworks surviving as the fruit of her psychologically healing work and the extension of her own duality. It is evident that her contributions to modern and contemporary art have provided springboards for other women to express their own traumas and find peace in excavating painful memories.

Appendix

Cover Image: Raimon Ramis, Louise Bourgeois in 1990, behind her marble sculpture Eye to Eye, 1970.

- Suzanne Muchnic, “Louise Bourgeois dies at 98; revered artist’s work was a ‘form of psychoanalysis’,” Los Angeles Times, June 1, 2010. https://www.latimes.com/local/obituaries/la-xpm-2010-jun-01-la-me-bourgeois-20100601-story.html.

- Michael Hatt and Charlotte Klonk. “Psychoanalysis,” in Art History: A Critical Introduction to its Methods, 177. Manchester University Press, 2006.

- Louise Bourgeois: No Trespassing. Directed by Nigel Finch. London: BBC, 1994.

- Roberta Smith, “Louise Bourgeois: Imagination Unfolds in All Dimensions,” The New York Times, September 27, 2017. https://www.nytimes.com/2017/09/27/arts/design/louise-bourgeois-imagination-unfolds-in-all-dimensions.html.

- Louise Bourgeois, Child Abuse: A Project by Louise Bourgeois, 1982, 45, Artforum, New York.

- Finch, Louise Bourgeois: No Trespassing.

- Frances Morris F, Louise Bourgeois Exhibition Catalogue, (New York: Rizzoli International Publications : March 18, 2008): 249.

- Louise Bourgeois, “Freud’s Toys,” The Sigmund Freud Antiquities: Fragment from a Buried Past at the University Art Museum of the State University of New York, Binghamton, first published in January 1990 in Artforum, vol. 28, no. 5, pp. 111-113.

- Duncan Ballantyne-Way, “Louise Bourgeois’ Child Abuse – The Rise of Spider-Woman”, Fine Art Multiple, 2017. https://fineartmultiple.com/blog/louise-bourgeois-child-abuse/.

- “Destruction of the Father,” The London List. https://www.thelondonlist.com/culture/louise-bourgeois.

- Rachel Cooke, “She’ll put a spell on you”, The Guardian, October 14 2007. https://www.theguardian.com/artanddesign/2007/oct/14/art.

- Deborah Wye, “Louise Bourgeois,” (New York: The Museum of Modern Art, 1982). https://www.moma.org/documents/moma_catalogue_2243_300296411.pdf,

- Zakia Uddin, “Louise Bourgeois at Freud Museum,” White Hot Magazine, May 2012, https://whitehotmagazine.com/articles/louise-bourgeois-at-freud-museum/2547.

- Tate Modern, “The Art of Louise Bourgeois.” https://www.tate.org.uk/art/artists/louise-bourgeois-2351/art-louise-bourgeois.

- Marie-Laure Bernadac, Louise Bourgeois (Flammarion, 2019), 149.

- Mignon Nixon. Fantastic Reality: Louise Bourgeois and a Story of Modern Art, MIT Press (2008).

- Alexander Potts, “Louise Bourgeois: Sculptural Confrontations,” Oxford Art Journal (Oxford University Press, 1999), vol. 22, no. 2, 51.

- Mieke Bal, “Autotopography: Louise Bourgeois as builder.” Biography, Vol. 25, No. 1 (Winter 2002): 184.

- Bal, “Autotopography,” 196.

- Nixon, “Losing Louise,” 126.

- Deborah Wye and Carol Smith, “The Prints of Louise Bourgeois,” New York: The Museum of Modern Art, 1994, p. 148.

- Louise Bourgeois. Directed by Camille Guichard, New York, 1993.

- Tate Modern, “The Art of Louise Bourgeois.”

- https://www.sothebys.com/fr/auctions/ecatalogue/lot.6.html/2019/contemporary-art-evening-auction-l19020

- Louise Bourgeois. “Statements from interview with Donald Kuspit,” In Destruction, 163.

- Louise Bourgeois: The Spider, The Mistress and The Tangerine. Directed by Amei Wallach and Marion Cajori (Zeitgeist Films: 2008).

- Louise Bourgeois. Diary note, 20 August 1993.

- Julia Nicoletta. “Louise Bourgeois’s Femmes-Maisons: Confronting Lacan,” Woman’s Art Journal, vol 12, no. 2, 1992, p.23.

- MoMA, “Louise Bourgeois: The Complete Prints & Books | Motherhood & Family,” MoMA, https://www.moma.org/s/lb/curated_lb/themes/motherhood_family.html.