Alchemy and the Feminine Mystique by May Chaib

November 15th, 2025

Ancestor of chemistry, the pseudo-scientific practice known as alchemy has a well-established relationship with art and entertainment. Naturally, the practice is far from the objective, pragmatic and empirical science we know today. Alchemy was infused with mystic philosophy and an artistic spirit, all while holding on to religious faith. Alchemy, at its core, aims to transcend nature, which is a central theme in creative practices. It’s about imitation and deconstruction, the creation of a new reality. Unsurprisingly, female alchemists have a long-ignored tradition of gender-influenced practices, underrepresented yet highly relevant. The historical context of Medieval times planted the seeds for a distinct feminine perspective on alchemy to blossom. Domestic and intuitive approaches challenged the male alchemical tradition, while also filling its gaps and expanding on hegemonic heritage and artistic exploration.

One of the most cited female alchemists to influence the iconography of the practice is Maria the Jewess. For context, alchemy can be defined as a practice that aims at the transformation of matter and substances. It takes two main forms, practical alchemy, which is mostly pharmaceutical. Elixirs, medicine and sometimes dyes are the products of it. Mystical or spiritual alchemy sees transformation as a metaphor for top of transformation of matter. It is more in tune with the divine. Maria the Jewess is understood to be the first alchemist to separate herself from spiritual matters. She was the founder of an academy in Egypt, practicing the typical alchemical goal of transmuting lead or other cheap metals into gold. Her inventions, such as the bain-marie (double boiler), remain immortalized in the alchemical sphere. Used to evenly heat up substances, it became an essential tool for the distillation, sublimation and purification processes used in alchemy, and later on chemistry, pharmaceutical practices and cooking.

Engraving of Maria the Jewess, 1617

Ancient Egypt was a potent land for alchemists. From this region stems Cleopatra the alchemist, student of Maria the Jewesse. She is said to be amongst one the four rare women capable of the philosopher’s stone. She invented the alembic practice, a distillation method using alchemical apparatus to separate a substance's components by vaporization and condensation. Cleopatra equates her work to the parental relation one has with their child. She often talks of birth and conception, relating motherly feelings to her alchemical projects. Alchemy is a protoscience that experiments with life, its creation and its transformation, to the point of almost personifying the discipline.

Ancient Egypt was a scientific hub, women were granted an amount of autonomy unseen in other civilizations of the time, which permitted them to contribute to technical innovations. Later on, in the early modern era, female alchemists slowly started replacing transmutation of metals with practices focused on cosmetics, medicine and the domestic sphere. In the 16th century, Isabella Cortese wrote and published a book of alchemical principles regarding medicine and cosmetic secrets titled I Secreti Della Signora Isabella Cortese. The 17th century saw La Chymie Charitable et Facile, en Faveur des Dames, a chemistry treatise aimed at women. Female practitioners gradually reshaped alchemy to fit into the feminine mold, a science aimed at maintaining appearances, a practice that stayed inclusive to female circles. Apothecaries often were confined to households, laboratories and workshops. Slowly, the spiritual and symbolic meaning started to dissipate. By blurring the lines between science and craft, they explored bodily knowledge and the transformation of the self. This form of alchemy is a consequence of rigid and reductive feminine standards; it, however, had its importance. Alchemists expanded on the idea of the practice beyond metallic transmutation; the concept of intimate alchemy owes its origins to women.

The 20th century saw a reinterpretation of these ancient alchemical and spiritual ideas through Swiss psychiatrist Carl Gustav Jung. He applies the concept of individuation to writings of the Middle Ages, which contextualizes alchemical symbols as psychological development. Take concepts like the furnace, dissolution or the unification of opposites, common in natural philosophy of the times, Jung argues these processes become internalized and self-integrated. But how does that relate to women? He believes that everyone contains masculine and feminine elements. The feminine, half that he calls anima, is essential for one’s “wholeness”. It is poetic in a sense; however, his approach reinforces hierarchies he claims to subvert. By framing “the feminine” as a mere tool for masculine self-discovery, Jung abstracts womanhood as a means to an end. He transforms that idea of intimate alchemy, which women created due to oppression, by decontextualizing the symbolisms and reframing them as anima – a force that can nurture men into self-improvement. Naomi Goldenberg points out this issue, arguing that the feminine remains just a metaphor, romantic but never fully realized.

Woodcut illustration of the masculine and feminine energy, 1625

This brings us to the idea of the feminine mystique, which romanticizes women all the while keeping them at a distance, unattainable and more symbolic and concrete. In Jung’s work and broader Western thought, the feminine embodies fear of physical presence, liking the idea of women but not women themselves. The mystical nature of alchemy becomes a perfect canvas to project onto women the societal fear of femininity, whilst also reappropriating what they bring into the world. The alchemist becomes admired, a figure of projection, almost a cipher. Historically, women were hard-working; they theorized, experimented and created in spite of their limitations and the societal attempts to erase their contributions. Hegemonic ideas attempt to dehumanize influential women, reducing them from people to concepts. This tension is echoed by Betty Friedan, who popularized the feminine mystique with her eponymous book, explaining how women were praised as nurturers but denied authority and any significant power. The paradox is illustrated in both psychology and alchemy: women are celebrated in theory but ignored in practice.

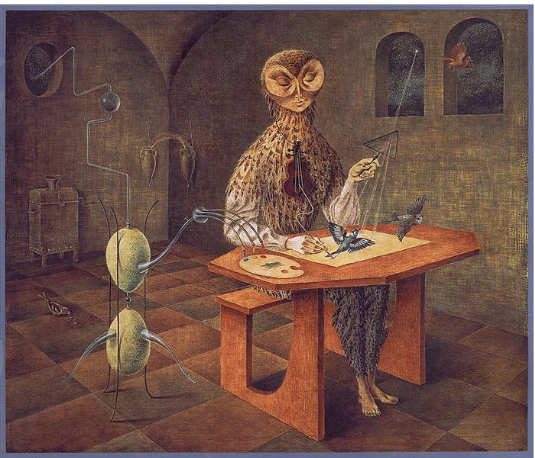

Hints of resistance and creativity, albeit remain, alchemy was reclaimed by women of the artistic surrealist movement. Through the previously established concept of transformation, Leonora Carrington and Remedios Varo expressed their creativity and explored their ever-changing personhood while tapping into alchemical symbolism to emphasize feminine agency. Varo and Carrington shared a deep friendship that was influential in their art as they developed a shared visual language, depicting alchemy and mysticism through womanhood. After WWII, they were exiled in Mexico and established themselves in the surrealist scene as subverters of the image of women as muses. In their work, they depict experimenters as active rather than passive symbols.

Despite this, external interpretations and critiques of their pieces often fetishize the feminine mystique, depicting the idea as somehow affirming. Reclaiming oppression is not always done in a way that is tasteful nor empowering. Many interpretations inadvertently repeat myths and reinforce the idea of female knowledge being intuitive, imaginative and spiritual. While those are by no means negative traits, they ignore the very real traces of women’s empirical alchemical research and their technical contributions. Mystical imagery is alluring; however, it's easy to slip into the territory of stereotypes even when being subversive.

Varos Remedio. Creation of Birds, 1957

Leonora Carrington. The House of Opposites, 1945

Nowadays, the intrigue around alchemy is alive and thriving in art and popular culture. The resurgence of witchcraft, esoterism and occult practices in the last few decades spotlights a collective yearning for sacredness, spirituality and community amongst women. Nevertheless, the feminine mystique persists in the contemporary era. If medieval alchemists looked to turn base matter into gold, then perhaps the task of modern feminists is to turn myth into history, to uncover the tangible creativity that lies beneath centuries of mystification.

Works Cited

Sack, Harald. “Mary the Jewess and the Origins of Chemistry.” SciHi Blog, May 8, 2020. http://scihi.org/mary-the-jewess-origins-chemistry/

Cohen, Stephen Michael. “Maria the Jewess.” The Shalvi/Hyman Encyclopedia of Jewish Women, 25 June 2021, jwa.org/encyclopedia/article/maria-jewess.

Cheney, Liana de Girolami. “Lavinia Fontana’s Cleopatra the Alchemist.” Journal of Literature and Art Studies, vol. 8, no. 8, Aug. 2018.

Cortese, Isabella. I secreti della Signora Isabella Cortese. Venice, 1561.

“Alchemy of Gender.” Quest Magazine, Theosophical Society in America, theosophical.org/publications/quest-magazine/alchemy-of-gender.

Jung, C. G. Aion: Researches into the Phenomenology of the Self. Translated by R. F. C. Hull, Princeton University Press, 1959. (Collected Works, Vol. 9, Part 2).

Jung, C. G. The Archetypes and the Collective Unconscious. Translated by R. F. C. Hull, Princeton University Press, 1968. (Collected Works, Vol. 9, Part 1).

Jung, C. G. Mysterium Coniunctionis: An Inquiry into the Separation and Synthesis of Psychic Opposites in Alchemy. Translated by R. F. C. Hull, Princeton University Press, 1963. (Collected Works, Vol. 14).

Goldenberg, Naomi R. Changing of the Gods: Feminism and the End of Traditional Religions. Beacon Press, 1979.

Goldenberg, Naomi R. “The Return of the Goddess: Jung, Feminism, and the End of Patriarchy.” Spring: A Journal of Archetype and Culture, vol. 5, 1981, pp. 108–119.

Friedan, Betty. The Feminine Mystique. W. W. Norton & Company, 1963.

Robinson, Elizabeth. Reframing the Occult-inspired Paintings of Leonora Carrington and Remedios Varo with Anti-Essentialist Methodology. M.A. thesis, Concordia University, December 2023.

Cohen, Stephen Michael. “Maria the Jewess.” The Shalvi/Hyman Encyclopedia of Jewish Women, 25 June 2021, jwa.org/encyclopedia/article/maria-jewess.

Cheney, Liana de Girolami. “Lavinia Fontana’s Cleopatra the Alchemist.” Journal of Literature and Art Studies, vol. 8, no. 8, Aug. 2018.

Cortese, Isabella. I secreti della Signora Isabella Cortese. Venice, 1561.

“Alchemy of Gender.” Quest Magazine, Theosophical Society in America, theosophical.org/publications/quest-magazine/alchemy-of-gender.

Jung, C. G. Aion: Researches into the Phenomenology of the Self. Translated by R. F. C. Hull, Princeton University Press, 1959. (Collected Works, Vol. 9, Part 2).

Jung, C. G. The Archetypes and the Collective Unconscious. Translated by R. F. C. Hull, Princeton University Press, 1968. (Collected Works, Vol. 9, Part 1).

Jung, C. G. Mysterium Coniunctionis: An Inquiry into the Separation and Synthesis of Psychic Opposites in Alchemy. Translated by R. F. C. Hull, Princeton University Press, 1963. (Collected Works, Vol. 14).

Goldenberg, Naomi R. Changing of the Gods: Feminism and the End of Traditional Religions. Beacon Press, 1979.

Goldenberg, Naomi R. “The Return of the Goddess: Jung, Feminism, and the End of Patriarchy.” Spring: A Journal of Archetype and Culture, vol. 5, 1981, pp. 108–119.

Friedan, Betty. The Feminine Mystique. W. W. Norton & Company, 1963.

Robinson, Elizabeth. Reframing the Occult-inspired Paintings of Leonora Carrington and Remedios Varo with Anti-Essentialist Methodology. M.A. thesis, Concordia University, December 2023.

Images

Maier, Michael. Symbola aureae mensae duodecim nationum. Frankfurt am Main: Lucas Jennis, 1617. Engraving of Maria the Jewess, early alchemist. Wellcome Library, London.

Jamsthaler, Herbrandt. Viatorium Spagyricum : Das ist ein gebenedeyter spagyrischer Wegweiser … Frankfurt am Main : Lucas Jennis, 1625. Woodcut illustration.

Varo, Remedios. Creation of the Birds. 1957, oil on masonite, Museo de Arte Moderno, Mexico City.

Carrington, Leonora. The House Opposite (La casa de enfrente). 1945, tempera on board, 33 × 82 cm, West Dean College of Arts & Conservation.