“Ceci n’est pas un viol” – Ornella Begalli

APRIL 11, 2016

Ornella Begalli is originally from Verona, Italy and is currently doing her Msc in Modern and Contemporary Art at the University of Edinburgh. She did her BA in English Literature and German at the University of Verona with one year exchange at the University of Edinburgh. Her dissertation focused on the influences of Post-Impressionism and Cubism on Virginia Woolf’s early novels. She is particularly interested in the relationship between literature and poetry with the visual arts and she is planning to write her master’s dissertation on this topic too.

Ornella Begalli est originaire de Vérone, Italie et est actuellement en Msc Art Moderne et Contemporain à l’université d’Edimbourg. Elle a fait son BA en Littérature Anglaise et Allemande à l’université de Vérone, au cours duquel elle a pu faire un an d’échange à l’étranger à l’université d‘Edimbourg. Sa dissertation se concentre sur les influences du post-impressionism et du cubism au sein des romans récents de Virginia Woolf. Elle est particulièrement intéressée par les relations entre les arts visuels et la littérature et poésie, et envisage d’écrire sa thèse de master sur ce sujet.

“I am interested in what the public does with it, which begins with the way they deal with it from the moment it’s disseminated.”(1)

The above is just a part of the interview that artist Emma Sulkowicz gave artnet on the 4th June 2015, following the release of her latest project: Ceci N’est Pas Un Viol. The artist, mostly famous as Mattress Girl, declared she would not reveal how the idea of the piece came to her mind, in order not to influence the way her audience would look at it. Given the importance of the figure of the viewer in this artwork we should not be surprised by her silence.

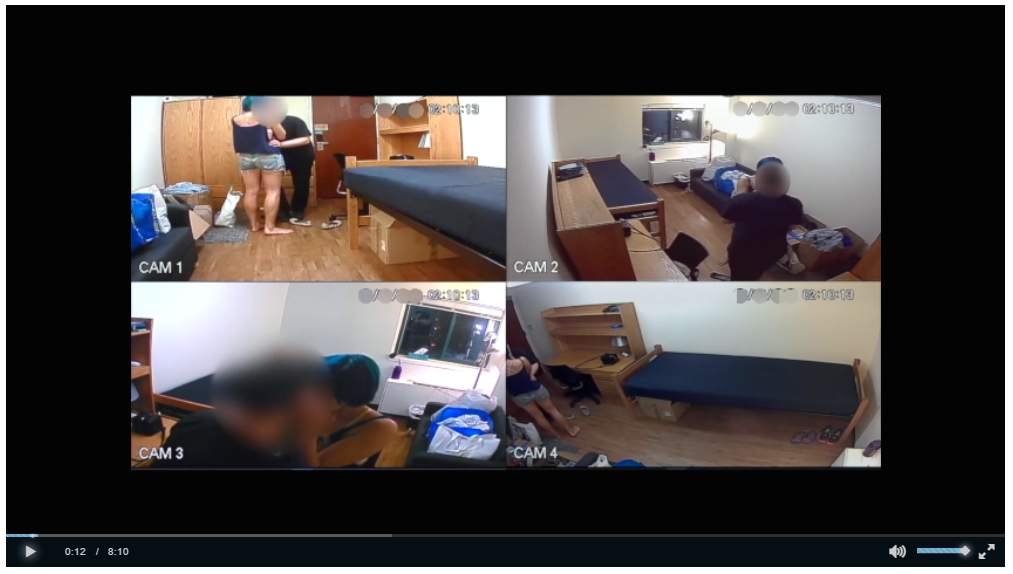

Using what can be considered the document of the Digital Era, a website, the artist wants to challenge her public’s view on rape, but not as anyone else thinks, by simply putting a harsh video right at the middle of the webpage. All the critiques and the scandal surrounding the piece are effectively just about the second part of it: a video depicting a supposedly unsimulated sex that actually, even if the artist states the opposite, does resemble rape. It is exactly because of this video that the entire artwork circulated all over the net, and that the day after its release the website was shut down by a cyber attack. What media and the majority of viewers did not notice is that the most important part of the work is the last one: the comment section. It is with this part that Sulkowicz wants to involve her public into the creative process and innovate the way rape culture can be discussed.

This paper will first provide an insight on two representations of rape from two different periods of the history of art, noticing how the spectator’s role (but also the artist’s one) has changed through the centuries. Following this, I will then focus on the form of art that remodeled the ‘90s, namely Internet Art, analyzing its development, problematics and positive sides. I will then direct my attention on Emma Sulkowicz, giving a brief overview of her previous piece and then examine Ceci N’est Pas Un Viol and how the artwork manages to revolutionize the relationship between the viewer and the Digital Era’s document.

Representation of rape: from Baroque to Performance Art

Gianlorenzo Bernini’s The Rape of Proserpina could easily be described as one of the most sensuous art pieces ever created. Every year, millions of tourists are immediately caught by its fleshy voluptuousness and fulfilling carnality. The sculptural group stands alone right in the middle of the Sala degli Imperatori of the Galleria Borghese in Rome and it is exactly this particular collocation that makes the visitor revolve around it in search of its every little aspect. Our eyes are caught by its magnetic theatricality, the pulsating dynamism, the striking rendering of the particulars. I venture to think that all these are the reasons why ̶ too busy wondering how Bernini managed to interpret in such a perfect way Proserpine’s despair or Pluto’s vigorous musculature ̶ visitors completely forget about what the artwork really is: rape.

Bernini’s representation of Ovid’s tale manages to romanticise and aestheticise a strongly dramatic event, twisting it to the point it is no longer seen as a crime. According to the myth, attracted by Proserpine’s beauty, Pluto just decided to abduct the girl to conduct her down to Hades, obviously, without asking her for permission. Even if in the 17th century Italy the word ‘rape’ meant ‘kidnapping’, the brutality of what is happening in the composition does not decrease at all. As many other pieces of this kind, the sculpture looks more as a portrayal of a “heroically idealized adventure of male self-realization in action”(2) than a savage act of violence. Accounts on why the sculpture creates this feeling of lure and sensuality instead of making us shiver could be many: possibly because Bernini just wanted to convey this message or, more likely, because the artist himself was a man. In this case, the viewer is almost mocked by the artist, overturned by the force of the composition he does not have the chance to focus on what the sculpture is actually presenting him with.

In his article “From Victim to Victor: Women Turn the Representation of Rape Inside Out”, G. Roger Denson states that since the Ancient Greek Era rape has always been one of the most popular themes in Western European Art. On all occasions, except for few instances, artistic representations of rape had literally always been portrayed by men. It is only from the mid ’60s of the 20th century that we can attend an about turn: men no longer want to give their contribution to the issue, while women can finally start working on this specific visual discourse. Probably supported by the spreading of the Second-wave feminism, artists such as Ana Mendieta, Suzanne Lacy, Yoko Ono and Tracey Emin “have elevated an art of ethics and empathy above aesthetics and dramatic tension as they turn the traditional male representations of rape inside out to display, effigize, mimic, and analogize the ravaged and broken bodies that betray the real-life effects of rape.”(3)

In March 1973, while artist Ana Mendieta was studying for a Masters in Intermedia at the Iowa University, 20-year-old student Sarah Ann Otten was assaulted, raped and then suffocated by a fellow student. Mendieta decided to artistically react to this brutal crime using her body in Untitled (Rape Performance). First staged as a performance and then later restaged twice to be documented in others outdoor spots, the artwork represents a personal response on violence against women. Few weeks after the sexual assault the artist asked friends and fellow students to visit her in her apartment, the audience was well aware they were going to be attending a performance piece but no one could have actually guessed what she would have presented them with. The door purposefully left slightly open, an almost entirely darkened room, Mendieta’s body tied, smeared with blood, undressed from the waist down, bent over a table: she had “recreated the scene as reported in the press.”(4) What the Cuban artist was looking for with this re-enactment was a reaction, she wanted the audience to reconsider their ideas on rape, to instigate a discussion on sexual assault against women and, as she later stated in an interview, that is exactly what she got: her public sat down, and started to talk about it. By not explicating herself, Mendieta gave her witnessing audience the opportunity to express what they think, succeeding “in creating another form of spectatorship, one that demanded its audience to react.”(5) I believe Mendieta wanted the discussion to go on way beyond her performance and to let this happen, she decided to document the other two works created in response of the crime. With the photographs capturing her bloodied half-naked body again, the artist puts her public on guard by showing them that no place is safe enough. Consequently, in this case the document becomes a sort of warning, a visual reminder made by the artist for her public. The relationship between the photographs and the viewer is purely platonic, the public is without any doubt pushed to give a response but his thoughts and words are not documented, there is no way to track his comments down.

Similarities between Mendieta and Sulcowicz’s artworks are easy to find, but what is relevant to my thesis is how they differentiate from one another. On one hand both the artists are considered to be feminists, the reaction they want from their audience is almost identical and they both portray themselves in the same vulnerable way ̶ yet it is from the medias they decided to use that we can really understand how different their approach is. Mendieta used performance art and photography, while Sulkowicz decided to convey her message through a digital form of document, she decided her artwork to be a website.

Internet Art

According to the legend, in December 1995 Slovenian artist Vuk Ćosić received an anonymous e-mail. From its content, which was nothing more than a confusing bunch of letters and numbers, Ćosić managed to grasp just one legible caption: “net.art”. The only decipherable fragment of the product of a completely casual accident had later become the name of a non-movement. This “informatic objet trouvé”(6) clearly linked the new trend to the “duchampian readymade”(7), showing us how influential other movements had been for the constitution of the Internet Art. Sharing visions on the immateriality of things as Conceptual Art and being attracted to the commercial side of culture as Pop Art, the term started to be used to indicate different activities:

Net.art stood for communications and graphics, e-mail, texts and images, referring to and merging into one another; it was artists, enthusiasts, and technoculture critics trading ideas, sustaining one another’s interest through ongoing dialogue. Net.art meant online détournements, discourse instead of singular texts or images, defined more by links, e-mails, and exchanges than by any “optical” aesthetics.(8)

The introduction of the first commercial web browser in 1994, the establishment of the World Wide Web in 1990 and the impressive widespread distribution of personal computers was starting to affect – both positively and negatively – every society in the world, opening up “a rich and exciting range of opportunities in the visual arts, as elsewhere – ones that seems to be infinite in their permutations.”(9)

The mid ‘90s witnessed the shift of the Internet as a media mainly used by professionals and experts, to a collective chance approachable by everyone who possessed an online access. Along with economists, politicians and of course hackers, artists immediately recognized the infinite possibilities of the web and started using it. First simply divulging other famous works of art by importing them on the net and then beginning to work in and with the net itself, in the years between 1994 and the end of the century, artistic practices on the web exponentially increased, websites and mailing lists rapidly proliferated. “By 1995, eight percent of all Web sites were produced by artists”(10) and just two years after, Internet art exploded.

The Oxford English Dictionary’s definition of “website” is as follows: “a document or a set of linked documents, usually associated with a particular person, organization, or topic, that is held on such a computer system and can be accessed as part of the World Wide Web.”(11) Sulkowicz’s artwork is surely not the first of its kind but it reveals in many ways the fresh approach of a Millenial to a relatively new type of artistic medium.

“The World Wide Web is only one of the media that make up the Internet. Internet artists have exploited plenty of other online protocols including e-mail, peer-to-peer instant messaging, videoconference, software, MP3 audio files, and text-only environments like MUDs and MOOs.”(12) The growing enthusiasm that started to surround the phenomenon also contributed to the diffusion of many questions regarding art’s future. How could Internet Art be collected? Is it possible to assess a specific value for one of its artworks? How could an Internet Art piece be preserved? And again of course, could this practices even be considered art? In his essay “Can Art History Digest Net Art?” art historian Julian Strallabass provides us with an insight on the complicated relationship between the established art world and Internet Art. Often put in the corner such as other relatively new media like video and photography, net.art is considered to be dangerous for the contemporary art market. Many professionals worried for the good conservation of “the mistery of its object”(13), find its lack of materiality, its peculiar transparency and immediacy irritating. Internet Art opens up to a new culture of participation, where viewers can become part of the work of art, sometimes strengthen the artwork but also making it more vulnerable to the assaults of the real world.

It is exactly this vulnerability that Emma Sulkowicz wanted to use in Ceci N’Est Pas Un Viol. She believes the only way to change the world is to show her weakness, that only through this the viewer could feel sympathetic and give his contribution to the piece.

Mattress Girl: Emma Sulkowicz

Emma Sulkowicz was born and raised in New York City. She attended college in New York City and got raped in New York City. The abuse is what led to Mattress Performance (Carry That Weight) a performance piece on which many things have been written on. The most disparate remarks has been given to the now 23-years-old artist: ‘pretty little liar’, ‘bitch’, ‘genius’, ‘feminist icon’, ‘shit feminist icon’. What eventually became her senior year thesis managed to unleash many discussions on a very delicate issue: what rape is, or even better, into which boundaries people marginalize rape. In August 2012, on her second year as a visual art student at Columbia University, Emma Sulkowicz got violated by one of her fellow students, a friend. The artist met Paul Nungesser during freshman orientation and by the end of the year they had become very close. Previous to the one sexual intercourse that created the foundation to her final dissertation, they did have other completely consensual encounters and, as they both stated, so it was the last one. I don’t want to go too deep on the argument, mainly because the accused was not found to be at fault, but evidently something occurred which really pushed Sulkowicz to react.

Begun on the first day of classes of her last year at university, the piece implicated Sulkowicz carrying a twin-sized mattress (very similar to the ones used by Columbia in its dorms) wherever she went on campus. The artist decided to formulate a list of rules to better define the development of the project. One of the most relevant is the one that does not let her directly ask for help but still allowing her to accept it whenever someone spontaneously offers to carry the weight of the mattress with her. “Analogies to the Stations of the Cross may come to mind, especially when friends or strangers spontaneously step forward and help her carry her burden, which is both actual and symbolic.”(14) Stating that the performance piece would have only came to and end when the student she was accusing would have been expelled, Sulkowicz just ended it in May 2015, when her and the mattress both attended her graduation ceremony.

The 21st Century Document: Ceci N’est Pas Un Viol

Mattress Performance had been on for just a couple of months when Sulkowicz, during her senior year’s winter break, started to develop her second public artwork. Released through Facebook by director Ted Lawson on the 3rd June 2015, Ceci N’est Pas Un Viol entirely exists on the internet. The titling of the work is clearly an homage to The Treachery of Images, one of the most famous paintings by surrealist artist René Magritte. The artwork shows a thorough depiction of a pipe and right below it, its subsequent written negation saying: “Ceci N’est Pas Un Pipe (This Is Not A Pipe)”. The opposition to the image created by the text is the artist’s attempt to highlight the enigmatic and often painful relationship between representation and realness. “Magritte’s painting, as Sulkowicz’s video, seeks to play with the audience’s perceptions of reality, with what they choose to see as true, and why.”(15) Sulkowicz is interested in challenging the viewer vision on rape, precisely she does not want them to ponder on the differences between what have happened to her and the simulated violence she is presenting, “but to understand the difference between their own definition of rape, how they’ve applied to her, and what rape actually is.”(16) The artwork is made up by three parts: an entrance web page, a video and a comment section. The first part is essentially the artist’s statement, she warns us about the allusions to rape in the piece and she makes clear that even if what happens in the video is completely consensual, it could still trigger thoughts of rape, inviting us to exit the website if anything makes us feel uncomfortable. Already from the first lines of the project, Sulkowicz places the gift of choice in our hands: “it’s about your decisions, starting now.”(17) She immediately elucidates what she wants from her piece, what the piece is and what she expects from the viewers: Sulkowicz’s wants to change the world “and that begins with you, seeing yourself.”(18) Right at the end of the introductory text there is a list of “a few questions to help you reflect”(19), divided into three categories: ‘searching’, ‘desiring’, ‘me’, with whom the artist “assigns your feelings to you, deciding that there is a right and wrong way to digest her art.”(20) The second part of the work is often believed to be the whole work itself, for it undoubtedly is the most “violent, explicit and hard to stomach”(21) section, it is also the most remembered by the viewer and obviously the part that caused the entire scandal around the piece. The authors of many articles decided not to play the video but in fact, even if I would never be able to experience it again, I do think my understanding of the artwork would have been split in half if I had not watched it. Because that is what it is: an experience that the artist submits us. The 8-minutes-long film starts with Sulkowicz and a blurred-face-man (actually an actor) who enter a dorm room and start having a consensual sexual encounter. After a few minutes the partner becomes violent, removes his condom and while she begs him to stop he begins slapping and choking her. The document, which is presented in split screen with four cameras recording from different angles of the room, has been more than once deemed as either a sex tape or a soft-porno, but as Hanna Rubin writes in her “This Is Not About Emma Sulkowicz’s Rape — It Is About You”, the enormous difference stands in the fact that even after the sex ends, the film goes on showing us a vulnerable woman curling up on a bed. The third and last part is what makes the artwork a well-constructed, complex piece of participatory art: the comment section. “Please be mindful of what you desire to gain from expressing yourself in the comment section below”(22) suggests the artist. Indeed, the real work of art is neither the video nor the opening part of the website for I believe the piece would not lose its power without them. It is the comment section that really manages to tell us what Sulkowicz is trying to do. Viewer could encounter the piece wherever on the internet, on social media, online papers, art critic’s reviews and as soon as this happen, they have to take a decision about what to do: to ignore the articles and to close the tab or to digit the name of the artwork and go on the website; once there to click on the play button of the video or just to focus on the questions, to leave a comment or simply scrolling down the thousands of them. The comment section of Ceci N’est Pas Un Viol is literally an archive of opinions, suggestions, insults, memories, answers. To leave a comment is pretty easy, you just need to log in into either your Twitter, Facebook, Google or Disqus accounts and then write. Comments can be sorted through three filters: ‘oldest’, ‘newest’ and ‘best’. Every comment can then be shared in every of this platforms enlarging the discussion, always relying on the engagement of the visitors. Again the viewer can define how this digital document will be displayed, he has the possibility to “vote” the comments he thinks are worth being read but he can also flag them as “inappropriate”. Meaningful is the fact that the comment section is the only part of the piece that can be shared without restrictions, while the video cannot be embedded into other pages.

Endnotes

(1) Cait Munro, ‘Emma Sulkowicz Speaks Out About Her New Video Performance’ interview with Emma Sulkowicz. Artnet, (June 2015): unpaginated.

(2) G. Roger Denson, ‘From Victim to Victor: Women turn the Representation of Rape Inside Out’, HuffingtonPost, (July 2011): unpaginated.

(3) Ibid.

(4) Elizabeth Manchester, ‘Untitled (Rape Scene), Tate, (October 2009): unpaginated.

(5) Emma Berentsen, ‘Efficacy Representations of Rape in Performances’, Academia, (2014): 17.

(6) Ileana Longo Goffo, ‘0100101110101101.ORG: arti mediatiche dentro e fuori la rete’, translated by the author, Academia, (2008): 38.

(7) Ibid.

(8) Rachel Greene, ‘Web Work: A History of Internet Art’, ArtForum, (May 2000): 162.

(9) William Vaughan, ‘History of Art in the Digital Age: Problems and Possibilities’, in Digital Art History, eds. Anna Bentkowska-Kafel, Trish Cashen and Hazel Gardiner (Bristol: Intellect, 2005), 3.

(10) Jon Ippolito, ‘Ten Myths of Internet Art’, Leonardo, Vol. 35, no. 5, (2002): 485.

(11) Oxford English Dictionary, s.v. “website”.

(12) Ippolito, ‘Ten Myths of Internet Art’, 486.

(13) Julian Stallabrass, ‘Can Art History Digest Net Art?’, Academia, (2009): 8.

(14) Roberta Smith, ‘In a Mattress, a Lever for Art and Political Protest’, The New York Times, (September 2014): unpaginated.

(15) Hanna Rubin, ‘This Is Not About Emma Sulkowicz’s Rape ̶ It Is About You’, The Forward, (June 2015): unpaginated.

(16) Rebecca Vipond Brink, ‘Emma Sulkowicz’s “Ceci N’est Pas Un Viol”: An Explainer’, The Frisky, (June 2015): unpaginated.

(17) Emma Sulkowicz, Ceci N’Est Pas Un Viol, 2015, Website.

(18) Ibid.

(19) Ibid.

(20) Alexandra Villareal, ‘Why Emma Sulkowicz’s ‘Ceci N’Est Pas Un Viol’ Is Very, Very Important’, Bullett Media, (June 2015): unpaginated.

(21) Sarah Seltzer, ‘Vile Comments Are The Most Important Part of Emma Sulkowicz’s Graphic New Video’, Flavorwire, (June 2015): unpaginated.

(22) Sulkowicz, Ceci N’Est Pas Un Viol.

(23) Ippolito, ‘Ten Myths of Internet Art’, 486.

(24) Douglas Davis, ‘The Work of Art in the Age of Digital Reproduction’, Leonardo, Vol. 28, no. 5, (1995): 384.

(25) Harm Rieske, ‘Audience as a medium: Internet Art, audience contribution and agency’, Academia, (2008): 26.

Bibliography

Berentsen, Emma. , ‘Efficacy Representations of Rape in Performances’. Academia, (2014), http://goo.gl/85I8J6 [accessed October 30, 2015]

Denson, Roger G. ‘From Victim to Victor: Women turn the Representation of Rape Inside Out’. HuffingtonPost, (July 2011), http://goo.gl/YnW9BA [accessed November 16, 2015]

Douglas, Davis. ‘The Work of Art in the Age of Digital Reproduction’. Leonardo, Vol. 28, no. 5, (1995), http://goo.gl/fS0PKp [accessed November 18, 2015]

Greene, Rachel. ‘Web Work: A History of Internet Art’. ArtForum, (May 2000), https://goo.gl/D8L27k [accessed November 22, 2015]

Ippolito, Jon. ‘Ten Myths of Internet Art’. Leonardo, Vol. 35, no. 5, (2002), http://goo.gl/MGZFB0 [accessed October 30, 2015]

Longo Goffo, Ileana. ‘0100101110101101.ORG: arti mediatiche dentro e fuori la rete’. Academia, (2008), http://goo.gl/E5sHa0 [accessed November 9, 2015]

Manchester, Elizabeth. ‘Untitled (Rape Scene). Tate, (October 2009), http://goo.gl/ycClIj [accessed October 30, 2015]

Munro, Cait. , ‘Emma Sulkowicz Speaks Out About Her New Video Performance’, Artnet, (June 2015), https://goo.gl/zEaQu1 [accessed November 9, 2015]

Rieske, Harm. , ‘Audience as a medium: Internet Art, audience contribution and agency’. Academia, (2008), http://goo.gl/EDJxBM [accessed November 16, 2015]

Rubin, Hanna. ‘This Is Not About Emma Sulkowicz’s Rape ̶ It Is About You’. The Forward, (June 2015), http://goo.gl/3AnCkE [accessed November 8, 2015]

Seltzer, Sarah. ‘Vile Comments Are The Most Important Part of Emma Sulkowicz’s Graphic New Video’. Flavorwire, (June 2015), http://goo.gl/engYl8 [accessed November 8, 2015]

Smith, Roberta. ‘In a Mattress, a Lever for Art and Political Protest’. The New York Times, (September 2014), http://goo.gl/egRuWh [accessed November 12, 2015]

Stallabrass, Julian. ‘Can Art History Digest Net Art?’. Academia, (2009), http://goo.gl/CYx9rI [accessed November 12, 2015]

Vaughan, William. ‘History of Art in the Digital Age: Problems and Possibilities’. In Digital Art History, edited by Anna Bentkowska-Kafel, Trish Cashen and Hazel Gardiner. Bristol: Intellect, 2005.

Vieal, Alexandra. ‘Why Emma Sulkowicz’s ‘Ceci N’Est Pas Un Viol’ Is Very, Very Important’. Bullett Media, (June 2015), http://goo.gl/6A3IZe [accessed November 8, 2015]

Vipond Brink, Rebecca. ‘Emma Sulkowicz’s “Ceci N’est Pas Un Viol”: An Explainer’. The Frisky, (June 2015), http://goo.gl/XvrvQu [accessed November 8, 2015]

Web Sources