Challenging the Male Gaze: The Portraiture of Alice Neel

MARCH 13, 2018

Throughout her long, eventful lifetime, Alice Neel experienced both extreme heartbreaks and successes, leading her to produce a large collection of work that is mostly autobiographical, and which demonstrates her unique obscure realist style which evolved and improved throughout the years.1 Born as a white American woman to a middle class family at the turn of the twentieth century, Neel’s life started out fairly smoothly. Her interest in the visual arts revealed itself early on, and around the age of twenty she began her formal artistic training, in which she excelled. During her time at school, she met Cuban artist Carlos Enríquez, the man she would marry shortly after, who would eventually spark her downwards emotional spiral. After she lost her first child and her husband ran off with her second she experienced a nervous breakdown, attempted suicide and was hospitalized for over a year. Fortunately, she was encouraged by the hospital to continue her art production for therapeutic measures. This was not the end of the hardships for Neel. After her release, she was involved with many male lovers – sometimes multiple at once – who treated her unfairly, “including one who slashed scores of her paintings. She had two more children… and later in life became a devoted, although eccentric, single mother and grandmother.”2 Despite this never-ending list of heartbreak, Neel’s career as an artist remained successful throughout her life, as she continuously exhibited her work across North America, finally establishing herself amongst other well-known artists in New York during the mid to late twentieth century. Neel was also steadily affiliated with the women’s liberation movement and the Communist party. She continued to participate in activism and exhibit her work up until her death in 1984.

Alice Neel’s left-wing and feminist values become evident through her art production, with the use of formal aspects, subject matter, and the way this subject matter is depicted. These values are especially visible in her portraits, her depictions of motherhood and her female nudes. It is these aspects of Neel’s work – her technical skill, use of realism and her biography – that make her stand out as such an influential icon to aspiring women artists from her lifetime up until today.

Alice Neel’s left-wing and feminist values are reflected in the selected individuals she deemed deserving of portraits. As she participated in activism and made her way up as a middle aged woman in the male-dominated New York art scene, she encountered and befriended many well-known artists and activists whom she asked to model for her. Many of the people she encountered were black activists, LGBTQ rights activists and other feminist women. As portraiture was Neel’s speciality, she would ask many of these individuals, whom she respected and thought of as accomplished creators, to sit for her. “Neel’s choices of sitters almost always reflected her own political and social concerns.”3 One portrait in particular, Linda Nochlin and Daisy (1973), depicts Linda Nochlin, a feminist art historian and author of the controversial essay “Why Have There Been No Great Women Artists?”, seated on a couch with her daughter Daisy. They are portrayed in a typical Neel fashion, with honesty and expressionistic lines. They are located in a domestic space, however the feeling elicited from the painting is anything but comfortable. The painting’s bright colours startle the viewer. Nochlin’s posture is tense, her crossed legs are unwelcoming, and her face and eyes, which appear a bit abnormally large in comparison to her body, stare directly at the viewer, challenging them. Daisy also looks directly at the viewer, but with a more innocent intention. This depiction is true to Nochlin as a strong woman and mother as well as to her profession as an art critic and historian. Neel represented them this way intentionally, as an act of respect and admiration. Nochlin later reciprocated the gesture by including Neel in the revolutionary exhibition Women Artists, 1550-1950 which she curated along with Ann Sutherland Harris.

Other feminist and activist individuals who appear in Neel’s series of portraits include Bella Abzug, a feminist woman and founder of the National Women’s Political Caucus, Jackie Curtis, a well-known transvestite actor, Faith Ringgold, a black feminist artist, and Annie Sprinkle, an American sex-positive feminist woman who is also a writer, actor and former prostitute. It is evident through the care and emotion in Neel’s technique that she did not only associate with these people, but found them well-deserving of being captured and commemorated in a painting. “In representations of women, she penetrated social artifice and dignified her subjects through a courageous, brutally honest approach to rendering an individual character.”4 She allowed her work, and therefore her chosen subjects, to speak to her personality and political beliefs.

Unlike most representations of motherhood in the traditional art historical canon, Neel’s paintings featuring soon-to-be-mothers and mothers with children present it in a non-romanticized and honest but yet positive light. Many historical artworks pertaining to motherhood depict it in an idealized way, with the woman as an unconditionally joyful Madonna, even when dealing with the difficult aspects of parenting. This was meant to encourage women to remain in their passive position as mothers, housekeepers and wives, and to ease men’s guilty consciences with the knowledge that their female counterparts were ‘happy’ in this position. Neel created her motherhood paintings from the perspective of a mother, rather than from that of the male gaze, projected onto the female subject. Leaving behind the notion of the “cherubic child and serene, smiling,”5 impermeable mother, Neel instead paints the mothers she knows honestly and unabashedly, capturing what motherhood is – for the most part – really like, in all its hardships and delights. She is “unafraid to reveal alongside the tenderness and joy mothers experience, the ambivalences, conflicts, and fears women face as mothers, too.”6 The topic of motherhood was very dear to Neel, which is not surprising given her history with children. She of all people knew that motherhood is not easy, nor always enjoyable.

A large portion of Neel’s oeuvre is made up of depictions of mothers, either expecting or with children. In these works, Neel focuses on the mundane, the mother’s experience, and the emotional connection between mother and child. These paintings “expose their inner experiences and unguarded private moments…”7 The faces of Neel’s mothers are not smiling, often with dark shadows cast on their faces, making them appear exhausted and aged. Yet, they also seem confident and unashamed to be seen this way. Sometimes Neel even used her brushstrokes and shading to capture the overwhelmed and fearful facial expressions of new mothers, not yet confident in their abilities. Again looking at Neel’s Linda Nochlin and Daisy, Nochlin’s stern, confrontational face, as well as her hand resting gently on her daughter, demonstrates the protective look of a mother. Most of Neel’s mother subjects share this same confrontational look.

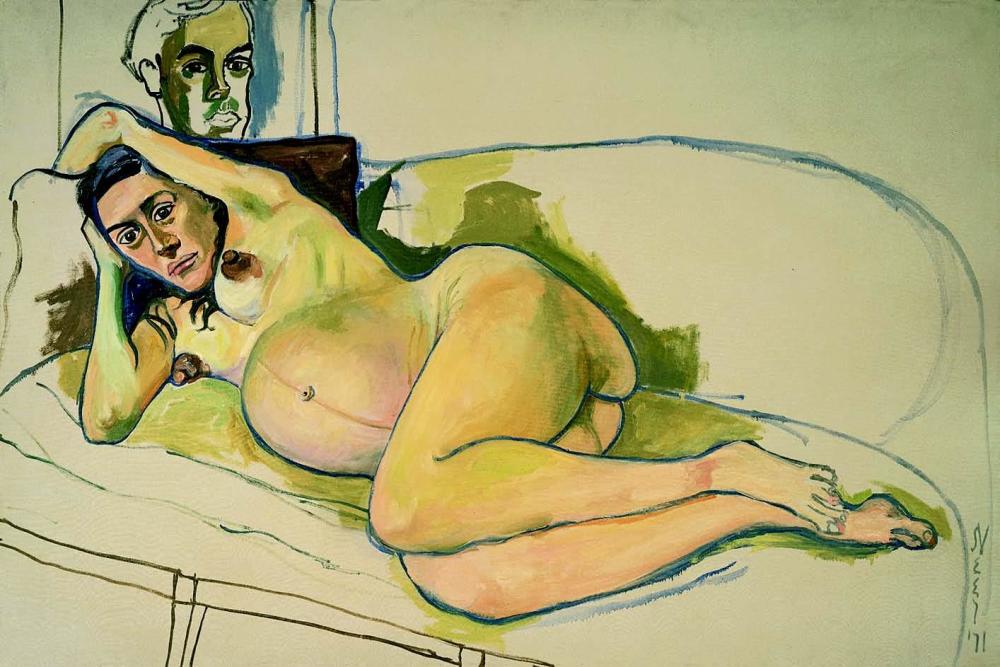

Neel not only painted the familiar aspects of motherhood but also those considered taboo. Breastfeeding mothers are the subjects of a few of her paintings, shocking viewers with the exposition of this necessary, natural, but yet somehow disapproved of phenomenon. Nude pregnant women were another favourite subject of Neel’s, making up a large portion of the work from her later years. These works question notions of sexuality related to pregnancy and motherhood, and challenge the traditional portrayal of femininity. When Neel first made these works, art viewers had become accustomed to constantly seeing the nude female body – but as it is usually depicted: healthy and fit to a certain degree, passive and modestly sexual. However, in Neel’s painting, Pregnant Woman (1971), depicting a very pregnant white woman on a couch, resting on her side with her arms raised to support her head, the woman has an ‘unideal’ body type but remains posed in a natural, subtly sexual way. She looks away from viewers, not inviting them to look at her. Likely for the first time, viewers experienced a female nude that was posed somewhat seductively, but was also an expecting mother. What would regularly be a object of male desire, could not really be so, as she was so obviously already ‘claimed’ by another man. The woman’s unavailability is highlighted further in Pregnant Woman, as the face of the assumed father can be seen on a painting hung on the wall behind the couch, looming protectively over the woman. These pregnant nudes challenged viewers’ perceptions and preconceived notions of sexuality, as it was thought that a woman was not meant to be openly sexy unless she was available to be desired.

Neel’s pregnant nudes were not the sole works that worked against the expectations of the male viewer. She often challenged the male gaze by depicting the female nude in a way that opposes its traditional characteristics. Up until recently, the female nude was a popular subject in artworks created by men, for the purpose of men’s viewing. The women were idealized, meaning that, for the majority, they were beautiful, passive objects of desire for the men in the artworks, and those viewing it. Instead of continuing this trend of helpless women in art, “Neel’s female nudes reverse, contradict and satirize this tradition most basically by reinterpreting the female nude as conscious and aware of the male gaze.”8 This is why many of her subjects stare directly back at the viewers, making them feel uneasy, as though they too are subjects of the gaze. The subjects’ body languages, shown through expressive brushstrokes, shading and palette, exude confidence.

Neel’s female nudes are uniquely hers, characterized by this awareness as well as her use of social realism, portraying these women as they were, flaws and all. This often meant the depictions would be somewhat unflattering, in terms of conventional beauty. She thought of this as painting her models in a way that, “respects and humanizes”9 them as opposed to objectifying them, as the male gaze does. Neel also countered the perfection and timelessness of the traditional female nude by including women of all ages in her portraits – for example, her self portrait at age eighty.

This honest and unconventional female nude – Self Portrait (1980) – is likely Neel’s most powerful action against the male gaze. In this work, Neel is seated in 3/4 profile on a striped chair. She leans slightly forward, with a paintbrush and rag in hand, engaged in her work. Following her female subjects’ trend, she actively looks back at her viewers, challenging them, “her face flushed… unself-conscious of her nudity and aging body.”10 This work exemplifies Neel’s appreciation for realness and imperfections, as her eighty year old body is noticeably sagging. She is at her most vulnerable, and yet, through her body language, appears completely bold and nonchalant. She wants viewers to know she is proud to have lived so long, despite her lingering depression.

An aging woman’s body is also a taboo image, unwanted by both the male and female gaze, yet Neel effortlessly subverts this notion by making viewers feel as though the only problem is that they are looking at her. Her aging nude body is not an object of desire, but she has put it on display, proving that women exist for more than just the pleasure of men.

Neel’s large body of work – made up of landscapes, still lifes and obviously, portraits – is extremely unconventional and full of emotion, a mirror of her life. Despite her serious emotional struggles and difficult life experiences, she succeeded in producing a plethora of influential paintings and drawings that helped change the way people look at art and the female body. Her personal experience, strong opinions and feminist beliefs are echoed in her art production, through her resistance to the traditional modes of painting and depicting subject matter. Her paintings of celebrity activists, unashamed mothers and unflattering female nudes have established her place as a strong, skilled, pioneering feminist artist of the twentieth century, and a well-deserved one at that.

Olivia Deresti-Robinson

FOOTNOTES

- “Biography,” Alice Neel, accessed March 3, 2017, http://www.aliceneel.com/biography/.

-

Denise Bauer, “Alice Neel’s Feminist and Leftist Portraits of Women,” Feminist Studies 28, no. 2 (2002): 386.

-

Ibid, 376.

-

Ibid, 385.

-

Denise Bauer, “Alice Neel’s Portraits of Mother Work,” NWSA Journal 14, no. 2 (2002): 102.

-

Ibid.

-

Ibid, 103.

-

Denise Bauer, “Alice Neel’s Female Nudes,” Woman’s Art Journal 15, no. 2 (1995): 21.

-

Ibid.

-

Ibid, 25.

All images from curiator.com