Electrifying Reality: Mechanical Objectivity in Brouillet’s Une leçon clinique à la Salpêtrière - Yolande Hanson

July 03, 2024

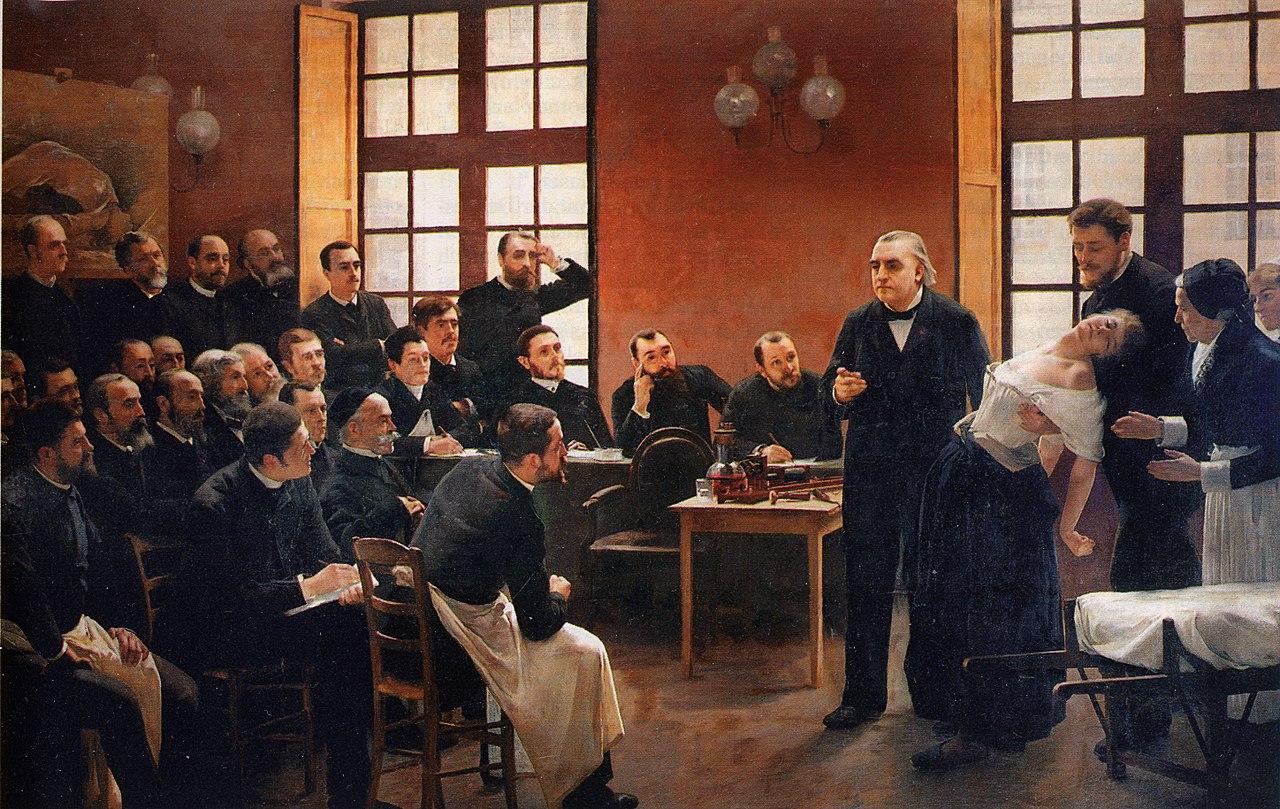

André Brouillet’s painting Une leçon clinique à la Salpêtrière (fig. 1) of a clinical lecture at Paris’ Pitié-Salpêtrière Hospital was a sensational success at the Salon of 1887. It depicts a brightly lit room of male students, physicians, and well-known figures of the time in observation of the patient Marie “Blanche” Wittman alongside the lecturing Dr Jean-Martin Charcot. Often called the “father” of neurology, Charcot gained acclaim for his research particularly on hysteria, the subject depicted in this painting. Une leçon clinique is representative of the period’s interest in technology, medicine, and the expansion of electrotherapy, which is evidenced by the centrally placed Du Bois-Reymond medical induction device and electrodes (fig. 2). As electrical tools came to the foreground of medical investigation, they were perceived to bestow mechanical objectivity in the hands of physicians, being capable of revealing the “real” muscular actions of the hysterical body. Through examining the role of the electrical device in Brouillet’s painting in connection to the male observers and the performance of hysteria, it can be shown that that this technology served as an attempt to “objectively” extend the physician’s hand in controlling, manipulating, and representing female psychopathology.

In a period where there was increased emphasis on the observation of patients to connect illnesses to a physiological lesion, hysteria occupied a difficult position. While hypothesized by Charcot as a lesion of the cerebral cortex, hysteria was ultimately a visual disease classified solely by its symptoms that included paralysis, seizures and social deviance. The importance of new technology like photography was thus paramount to accurately capture and document it. As Brauer writes, photographing hysterics was highly connected to electrotherapy as both novel inventions facilitated the emergence of a visual culture of hysteria that valued theatrical, mechanized and automated gestures. Indeed, Charcot’s use of metallotherapy evolved out of Duchenne de Boulogne’s mid-nineteenth century photographs that invoked certain facial expressions through electric current. By centralizing the electrical apparatus and contorting Wittman’s body, Brouillet utilized the public’s understanding of hysteria to craft a mechanical spectacle. The dark audience of male figures starkly contrast with Wittman, whose chest is illuminated as if by a stage light. The accompanying female figures amplify the theatricality by preparing for her potential collapse. With Wittman’s hips thrust forward, her neck exposed, and her breasts concealed by a flimsy blouse, Brouillet hints at the erotic and sensational associations of the disease that generated public interest. Through centralizing the electrotherapy device and automating Wittman’s gestures, Brouillet demonstrates how electricity facilitated a performance of hysteria for both the doctors trying to understand its scientific basis, and for the voyeuristic masses.

Further, Une leçon clinique alludes to the use of technology to “freeze” Blanche Wittman’s symptoms for the audience’s observation. As is evidenced by her contorted left hand, arched back, and closed eyes, Wittman was likely meant to be portrayed in a state of unconsciousness or somnambulism, which was believed by Charcot to be the final phase of a hysterical episode, succeeding the first, lethargy, and the second, catalepsy. Hunter points out that the head of the electrical unit at the Salpêtrière, Dr Vigouroux, is seated in the front row in Brouillet’s painting. This could suggest that he has just laid down the rheophore wand of the Du Bois-Raymond device in the moments preceding to mold Wittman’s expression for the crowd of eager observers. The rheophore was believed to charge the skin locally with electricity, allowing for what Duchenne described as the detection of small muscular movements “better than the anatomist’s scalpel ever could.” In alluding to the use of the Du Bois-Raymond machine to manipulate Wittman’s body, Brouillet’s painting allows for the audience to be privy to what they believed were the “real” symptoms of pathology.

The Du Bois-Raymond device also contributes to the status and prestige of the painting, thereby authenticating the objectivity and scientific rigour of Charcot’s methods. Charcot believed that electrotherapy could be an extension of hypnosis, a therapeutic procedure that involved the doctor facilitating the symptoms of hysteria on command to the hysterical patient. While this could equally control the state of the hysteric and “freeze” her symptoms, electric induction was considered a more mechanically objective validation of the hypnotic process. As hypnosis and Charcot’s lectures were highly theatrical, Brouillet’s insertion of a Du Bois-Raymond device makes a clear distinction that the lecture was an objective and serious endeavour. As Hunter notes, Brouillet’s inclusion of electricity both through the metallotherapy device and the large gaslights on the walls all function to communicate the modernity and status of the medical space. The bright light of the room, allowing for the rational gazes of the medical men on their female subject, also metaphorically suggest the illumination of knowledge and scientific rigour. In sum, while Wittman’s pose and the male assistant’s tight grip on her blouse carry sensational and erotic overtones, Brouillet’s scene authorizes these gestures under the guise of objectivity.

While the Du Bois-Raymond device was fashioned to be a symbol of objectivity and for enhancing empirical observation, this purpose in Brouillet’s painting is in tension with the fact that the machine was, in reality, for representing hysteria. Brouillet’s theatre-like composition with the bright illumination upon Wittman’s bosom, the gazes of the scientific men, and the mechanical power of the Du Bois-Raymond device grasp at a perfect objectivity. However, the entire performance through electrical induction ultimately serves to manipulate Wittman’s state such that her hysterical manifestation could be transformed into a diagnostic classification by the men present. It is only through the mass of male bodies gazing at Wittman and ascribing a label to her state that the hysteria of Wittman’s body was made “real” at all. The contrived theatricality depicted in Brouillet’s painting is a clear performance in which Wittman plays an assigned role for the male viewers who corroborate it. The Du Bois-Raymond device in Une leçon clinique can therefore be seen as a tool in facilitating the physician’s voyeurism of a purely visual illness. As such, it serves as a mechanical extension of the physician’s own involvement in representing female psychopathology, thus further fabricating the presence of the disease in its attempt at demonstrating the “real”.

Footnotes

1. Mary Hunter, “Hysterical realisms at the Salpêtrière: images, objects, and performances chez Dr Charcot,” in The Face of Medicine: Visualizing Medical Masculinities in late Nineteenth-Century Paris (Manchester: Manchester University Press, 2016), 166.

2. Natasha Ruiz-Gomez, “The Model Patient: Observation and Illustration at the Musée Charcot,” in Visualizing the Body in Art, Anatomy, and Medicine since 1800, ed. Andrew Graciano (New York: Routledge, 2019), 203.

Ruiz-Gomez, “The Model Patient,” 203.

3. Roy Porter, “The Body and the Mind, the Doctor and the Patient: Negotiating Hysteria,” in Hysteria Beyond Freud (Berkeley: University of California Press, 1993), 227.

4. Francesco Brigo et al., “Jean-Martin Charcot’s Medical Instruments: Electrotherapeutic Devices in La Lecon Clinique à la Salpêtrière,” Journal of the History of the Neurosciences 30, no. 1 (2021): 96, https://doi.org/10.1080/0964704X.2020.1775391.

5. Georges Didi-Huberman, Invention of hysteria: Charcot and the photographic iconography of the Salpêtrière (Cambridge: MIT Press, 2003), 199.

6. Didi-Huberman, Invention of hysteria, 71.

7. Hunter, “Hysterical realisms,” 167.

8. Fae Brauer, “Capturing Unconsciousness: The New Psychology, Hypnosis and the Culture of Hysteria,” in A Companion to Nineteenth-Century Art: From Revolution to World War, ed. Michelle Facos (Hoboken: John Wiley & Sons, 2018), 250.

9. Didi-Huberman, Invention of hysteria, 196.

10. Ruiz-Gomez, “The Model Patient,” 203.

11. Ruiz-Gomez, 205.

12. Brauer, “Capturing Unconsciousness,” 251.

13. Hunter, “Hysterical Realisms,” 225.

14. Didi-Huberman, Invention of hysteria, 196.

15. Hunter, “Hysterical Realisms, 214.

16. Hunter, “Hysterical Realisms,” 226.

17. Hunter, 183.

18. Ruiz-Gomez, 208.

19. Didi-Huberman, Invention of hysteria, 242.

Bibliography

Brauer, Fae. “Capturing Unconsciousness: The New Psychology, Hypnosis and the Culture of Hysteria.” In A Companion to Nineteenth-Century Art: From Revolution to World War, edited by Michelle Facos, 243-262. Hoboken: John Wiley & Sons, 2018.

Brigo, Francesco et al. “Jean-Martin Charcot’s Medical Instruments: Electrotherapeutic Devices in La Lecon Clinique à la Salpêtrière.” Journal of the History of the Neurosciences 30, no. 1 (2021): 94-101. https://doi.org/10.1080/0964704X.2020.1775391.

Didi-Huberman, Georges. Invention of hysteria: Charcot and the photographic iconography of the Salpêtrière. Cambridge: MIT Press, 2003.

Hunter, Mary. “‘Effroyable Réalisme’: Wax, Femininity, and the Madness of Realist Fantasies.” RACAR: Revue d’art Canadienne / Canadian Art Review 33, no. 1/2 (2008): 43–58.

Hunter, Mary. “Hysterical realisms at the Salpêtrière: images, objects, and performances chez Dr Charcot.” In The Face of Medicine: Visualizing Medical Masculinities in Late Nineteenth-Century Paris, 166-241. Manchester: Manchester University Press, 2016.

Porter, Roy. “The Body and the Mind, the Doctor and the Patient: Negotiating Hysteria.” In Hysteria Beyond Freud, 225-285. Berkeley: University of California Press, 1993.

Ruiz-Gomez, Natasha. “The Model Patient: Observation and Illustration at the Musée Charcot.” In Visualizing the Body in Art, Anatomy, and Medicine since 1800, edited by Andrew Graciano, 203-232. New York: Routledge, 2019.

Sekula, Allan. “The Body and the Archive.” October 39 (1986): 3–64. https://doi.org/10.2307/778312.

In a period where there was increased emphasis on the observation of patients to connect illnesses to a physiological lesion, hysteria occupied a difficult position. While hypothesized by Charcot as a lesion of the cerebral cortex, hysteria was ultimately a visual disease classified solely by its symptoms that included paralysis, seizures and social deviance. The importance of new technology like photography was thus paramount to accurately capture and document it. As Brauer writes, photographing hysterics was highly connected to electrotherapy as both novel inventions facilitated the emergence of a visual culture of hysteria that valued theatrical, mechanized and automated gestures. Indeed, Charcot’s use of metallotherapy evolved out of Duchenne de Boulogne’s mid-nineteenth century photographs that invoked certain facial expressions through electric current. By centralizing the electrical apparatus and contorting Wittman’s body, Brouillet utilized the public’s understanding of hysteria to craft a mechanical spectacle. The dark audience of male figures starkly contrast with Wittman, whose chest is illuminated as if by a stage light. The accompanying female figures amplify the theatricality by preparing for her potential collapse. With Wittman’s hips thrust forward, her neck exposed, and her breasts concealed by a flimsy blouse, Brouillet hints at the erotic and sensational associations of the disease that generated public interest. Through centralizing the electrotherapy device and automating Wittman’s gestures, Brouillet demonstrates how electricity facilitated a performance of hysteria for both the doctors trying to understand its scientific basis, and for the voyeuristic masses.

Further, Une leçon clinique alludes to the use of technology to “freeze” Blanche Wittman’s symptoms for the audience’s observation. As is evidenced by her contorted left hand, arched back, and closed eyes, Wittman was likely meant to be portrayed in a state of unconsciousness or somnambulism, which was believed by Charcot to be the final phase of a hysterical episode, succeeding the first, lethargy, and the second, catalepsy. Hunter points out that the head of the electrical unit at the Salpêtrière, Dr Vigouroux, is seated in the front row in Brouillet’s painting. This could suggest that he has just laid down the rheophore wand of the Du Bois-Raymond device in the moments preceding to mold Wittman’s expression for the crowd of eager observers. The rheophore was believed to charge the skin locally with electricity, allowing for what Duchenne described as the detection of small muscular movements “better than the anatomist’s scalpel ever could.” In alluding to the use of the Du Bois-Raymond machine to manipulate Wittman’s body, Brouillet’s painting allows for the audience to be privy to what they believed were the “real” symptoms of pathology.

The Du Bois-Raymond device also contributes to the status and prestige of the painting, thereby authenticating the objectivity and scientific rigour of Charcot’s methods. Charcot believed that electrotherapy could be an extension of hypnosis, a therapeutic procedure that involved the doctor facilitating the symptoms of hysteria on command to the hysterical patient. While this could equally control the state of the hysteric and “freeze” her symptoms, electric induction was considered a more mechanically objective validation of the hypnotic process. As hypnosis and Charcot’s lectures were highly theatrical, Brouillet’s insertion of a Du Bois-Raymond device makes a clear distinction that the lecture was an objective and serious endeavour. As Hunter notes, Brouillet’s inclusion of electricity both through the metallotherapy device and the large gaslights on the walls all function to communicate the modernity and status of the medical space. The bright light of the room, allowing for the rational gazes of the medical men on their female subject, also metaphorically suggest the illumination of knowledge and scientific rigour. In sum, while Wittman’s pose and the male assistant’s tight grip on her blouse carry sensational and erotic overtones, Brouillet’s scene authorizes these gestures under the guise of objectivity.

While the Du Bois-Raymond device was fashioned to be a symbol of objectivity and for enhancing empirical observation, this purpose in Brouillet’s painting is in tension with the fact that the machine was, in reality, for representing hysteria. Brouillet’s theatre-like composition with the bright illumination upon Wittman’s bosom, the gazes of the scientific men, and the mechanical power of the Du Bois-Raymond device grasp at a perfect objectivity. However, the entire performance through electrical induction ultimately serves to manipulate Wittman’s state such that her hysterical manifestation could be transformed into a diagnostic classification by the men present. It is only through the mass of male bodies gazing at Wittman and ascribing a label to her state that the hysteria of Wittman’s body was made “real” at all. The contrived theatricality depicted in Brouillet’s painting is a clear performance in which Wittman plays an assigned role for the male viewers who corroborate it. The Du Bois-Raymond device in Une leçon clinique can therefore be seen as a tool in facilitating the physician’s voyeurism of a purely visual illness. As such, it serves as a mechanical extension of the physician’s own involvement in representing female psychopathology, thus further fabricating the presence of the disease in its attempt at demonstrating the “real”.

Footnotes

1. Mary Hunter, “Hysterical realisms at the Salpêtrière: images, objects, and performances chez Dr Charcot,” in The Face of Medicine: Visualizing Medical Masculinities in late Nineteenth-Century Paris (Manchester: Manchester University Press, 2016), 166.

2. Natasha Ruiz-Gomez, “The Model Patient: Observation and Illustration at the Musée Charcot,” in Visualizing the Body in Art, Anatomy, and Medicine since 1800, ed. Andrew Graciano (New York: Routledge, 2019), 203.

Ruiz-Gomez, “The Model Patient,” 203.

3. Roy Porter, “The Body and the Mind, the Doctor and the Patient: Negotiating Hysteria,” in Hysteria Beyond Freud (Berkeley: University of California Press, 1993), 227.

4. Francesco Brigo et al., “Jean-Martin Charcot’s Medical Instruments: Electrotherapeutic Devices in La Lecon Clinique à la Salpêtrière,” Journal of the History of the Neurosciences 30, no. 1 (2021): 96, https://doi.org/10.1080/0964704X.2020.1775391.

5. Georges Didi-Huberman, Invention of hysteria: Charcot and the photographic iconography of the Salpêtrière (Cambridge: MIT Press, 2003), 199.

6. Didi-Huberman, Invention of hysteria, 71.

7. Hunter, “Hysterical realisms,” 167.

8. Fae Brauer, “Capturing Unconsciousness: The New Psychology, Hypnosis and the Culture of Hysteria,” in A Companion to Nineteenth-Century Art: From Revolution to World War, ed. Michelle Facos (Hoboken: John Wiley & Sons, 2018), 250.

9. Didi-Huberman, Invention of hysteria, 196.

10. Ruiz-Gomez, “The Model Patient,” 203.

11. Ruiz-Gomez, 205.

12. Brauer, “Capturing Unconsciousness,” 251.

13. Hunter, “Hysterical Realisms,” 225.

14. Didi-Huberman, Invention of hysteria, 196.

15. Hunter, “Hysterical Realisms, 214.

16. Hunter, “Hysterical Realisms,” 226.

17. Hunter, 183.

18. Ruiz-Gomez, 208.

19. Didi-Huberman, Invention of hysteria, 242.

Bibliography

Brauer, Fae. “Capturing Unconsciousness: The New Psychology, Hypnosis and the Culture of Hysteria.” In A Companion to Nineteenth-Century Art: From Revolution to World War, edited by Michelle Facos, 243-262. Hoboken: John Wiley & Sons, 2018.

Brigo, Francesco et al. “Jean-Martin Charcot’s Medical Instruments: Electrotherapeutic Devices in La Lecon Clinique à la Salpêtrière.” Journal of the History of the Neurosciences 30, no. 1 (2021): 94-101. https://doi.org/10.1080/0964704X.2020.1775391.

Didi-Huberman, Georges. Invention of hysteria: Charcot and the photographic iconography of the Salpêtrière. Cambridge: MIT Press, 2003.

Hunter, Mary. “‘Effroyable Réalisme’: Wax, Femininity, and the Madness of Realist Fantasies.” RACAR: Revue d’art Canadienne / Canadian Art Review 33, no. 1/2 (2008): 43–58.

Hunter, Mary. “Hysterical realisms at the Salpêtrière: images, objects, and performances chez Dr Charcot.” In The Face of Medicine: Visualizing Medical Masculinities in Late Nineteenth-Century Paris, 166-241. Manchester: Manchester University Press, 2016.

Porter, Roy. “The Body and the Mind, the Doctor and the Patient: Negotiating Hysteria.” In Hysteria Beyond Freud, 225-285. Berkeley: University of California Press, 1993.

Ruiz-Gomez, Natasha. “The Model Patient: Observation and Illustration at the Musée Charcot.” In Visualizing the Body in Art, Anatomy, and Medicine since 1800, edited by Andrew Graciano, 203-232. New York: Routledge, 2019.

Sekula, Allan. “The Body and the Archive.” October 39 (1986): 3–64. https://doi.org/10.2307/778312.