Frida Kahlo, Teresa Margolles, and Death as Transgression

- Michaёlle Lahaye

March 26, 2024

As humanity’s inescapable transition to a dimension completely unknown to the living, death can be qualified as surreal. Yet, to some Mexican female artists, death is a very palpable aspect of the human condition that is deeply ingrained in both individual and collective consciousnesses. Through their work, Frida Kahlo and Teresa Margolles notably use the theme of death to position themselves within an artistic tradition that has historically snuffed out the conversations sparked by female artists. In this essay, I will demonstrate the ways in which Kahlo and Margolles transgressively exploit the theme of death in their work, respectively through the illumination of inner narratives and the denunciation of violence related to drug trafficking in Mexico. To do so, I will discuss Kahlo’s The Dream (1940) and Margolles’ What Else Could We Talk About? (2009).

When examining the work of Mexican female artists, it is crucial to underline the importance of surrealism’s role in fostering Mexican female artistry, while noting its discriminatory limitations. Fathered by French writer André Breton, surrealism’s beginnings were characterized by the development of psychic automatism, an art-making method that aimed for the suppression of reason and conventional thought to make way for the ideas brought forth by the human subconscious. The surrealist concern for the subconscious is rooted in Freudian theory, according to which dreams and other manifestations of the unconscious mind consist in an essential source of revelations pertaining to the understanding of human emotions otherwise repressed.1 Pictorially, this artistic method led to the creation of dream-like, illogical imagery, where time is often suspended and unrelated figures are juxtaposed.2 Following his multiple visits to Mexico, Breton described the country as a “constellation of seduction and dreams” and a world where surrealism could flourish.3 Interestingly, it is the “primitivity” of Mexico, contained in its people, fauna, and flora, that led to his fascination with the country’s culture and art production, as well as to his perspective of the country as surrealist.4 One could argue that Breton’s infatuation with Mexico’s surrealist “primitivity” stems from a Western paternalist gaze, which inherently views the other as illogical and, therefore, as captivating. Parallelly, Breton believed Indigenous female artists like Frida Kahlo and María Izquierdo to embody the essence of surrealism; their femininely “naïve” and “untrained” minds, which grew away from the Western world and its “advancements,” represented the rawness of humanity and a purer form of expression.5 Consequently, the mid-20th century saw a growing interest in showcasing the work of Mexican female artists—especially those who somehow responded to the surrealist quest. Kahlo’s work was notably exhibited at the International Exhibition of Surrealism held in Mexico City in 1940 even though she had repeatedly stated throughout her lifetime that she did not identify as a surrealist.6 7 Following this idea, although the arena of surrealism allowed Mexican female artistry to flourish, it is undeniable that the European art world’s interest in these artists was tinted with the misogynistic and racist perspective that prevailed in the Western world. Next to the fulfillment of a Western artistic fantasy of female primitivity, it seemed like the assertive self-fashioning of Mexican female artists did not weigh much.

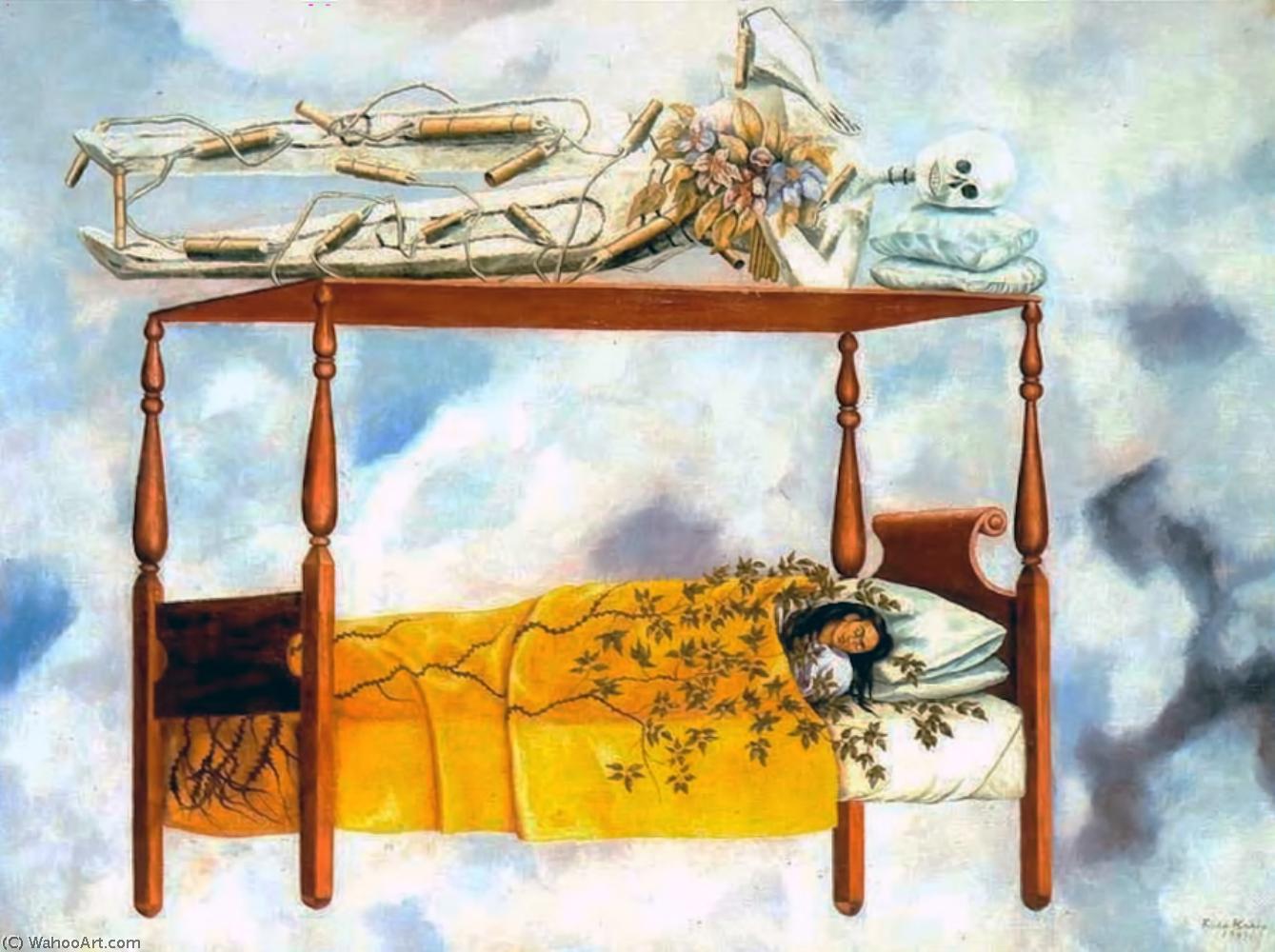

Formally speaking, Kahlo’s The Dream depicts a wooden canopy bed, in which the artist herself is represented, sleeping (fig. 1). She is dressed in a white garment, her head resting on two pillows while her body is covered with a large yellow blanket. A leafed plant climbs over the blanket, taking its roots under the footboard. On top of the bed, a skeleton is depicted in a position similar to Kahlo’s, although somewhat more rigid and robot-like. Their skull is also resting on two pillows, their naked body this time covered with an explosive apparatus. With their right hand, they are holding a bouquet of pastel-coloured flowers near their chest. The background of the artwork’s composition is formed by a dimensional, cloudy setting, making the bed appear as if it is floating in the sky.

At first glance, one could certainly argue that The Dream possesses a surrealist quality for it depicts a fantastical, unearthly scene. Even if one was to ignore its title, the artwork resembles a dreamscape via the representation of a bed floating in a cloudy sky, as well as the artist’s reference to sleep. Yet, a mindful understanding of Kahlo’s oeuvre and biography suggests the depiction of an inner, personal narrative that is fully rooted in reality. Despite artists like Breton categorizing Kahlo as a surrealist, there is nothing surreal about any of her works, for they are “pieces of her life.”8 The artist’s depiction of the theme of death in The Dream, marked by the representation of a skeleton, is to be understood in relation to her own life experience, which was traversed by—but surely not limited to—many traumatic events and a great presence of pain.9 Considering the physical and psychological suffering—her illnesses, disabilities, accidents, abortions, and tumultuous romantic relationship with Diego Rivera—that punctuated her life, I argue that the superposition of a skeleton over Kahlo’s body serves as the representation of death looming over her, patiently waiting to grant her damaged body its final wish.10 Moreover, the presence of two contrasting figures in the artwork, one alive and one dead, can be related to Kahlo’s interest in the concept of duality. Like the two mirrored subjects in Kahlo’s The Two Fridas (1939), the two superposed subjects in The Dream reflect the duality of the artist’s humanity, this time encapsulated within life and death. Most importantly, it is worthy to note that the artist’s depiction of the theme of death strongly differs from the depiction of similarly large existential themes within other modern art production in Mexico, making this artwork subversive in its tackling of the theme. Just a couple decades prior to Kahlo’s creation of The Dream, muralism’s three star artists—Diego Rivera, José Clemente Orozco, and David Alfaro Siqueiros—began creating their massive, state-sponsored murals depicting mega-narratives, which discussed complex themes such as class, labour, and corruption. Unlike these murals, Kahlo’s The Dream did not aim to fulfill a social purpose; the artist’s conception of death is not represented in an effort to appeal to a national mass. Rather, Kahlo’s depiction of death is meant to share a slice of her life with her viewers. Following this idea, Kahlo’s non-social treatment of death and her centering of her own life experience in The Dream—challenging a societal expectation of female selflessness—marks the transgressive nature of her work, which went against the grain of the Mexican modern art world.

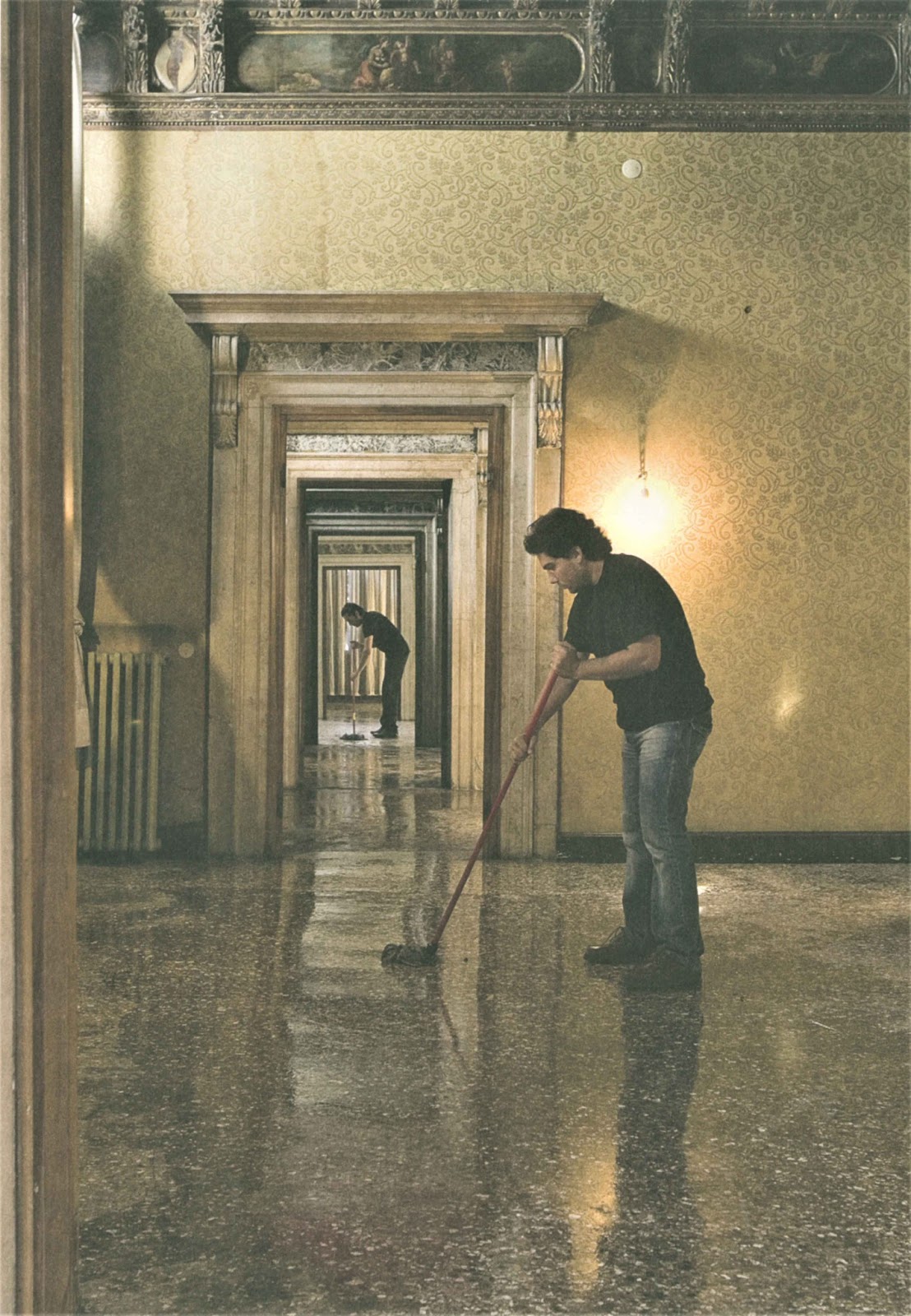

Through its blend of ready-made and performance art, Margolles’ What Else Could We Talk About? is formally divergent from Kahlo’s painting of The Dream. Exhibited as the artist’s contribution for the Mexican Pavilion of the Venice Biennale of 2009, the artwork was presented in the Palazzo Rota Ivancich—a spacious, Baroque-style palace—characterized by high ceilings, marble floors, and intricately ornamented doorways. The Biennale’s visitors were invited to silently walk through a series of rooms in which large pieces of cloth were hung on the walls. The cream-coloured pieces of cloth were completely soaked in a blood-like substance, forming dry, irregular stains (fig. 2). In each room, a person could be seen cleaning the floor with a mop (fig. 3).

It was only after viewing the artwork that the Biennale’s visitors were told the blood soaked into these pieces of cloth was real. In fact, these very pieces of cloth had previously served to clean the puddles of biological waste left by the corpses of victims of drug trafficking in the streets of Mexico’s urban agglomerations. The individuals mopping the marbled floors of the palace were members of the victims’ families, whom Margolles had invited to perform as a part of the artwork.11 Consequently, What Else Could We Talk About? builds a direct bridge between death and the viewer through the presentation of ready-made objects that were in direct contact with the bodily secretions of murdered individuals and the presence of those who mourn them, offering a tangible manifestation of the violence to which countless Mexicans have succumbed. In other words, the artwork curiously displays the use of death as a medium. Unlike Kahlo’s introspective exploration in The Dream, the use of the theme of death in Margolles’ What Else Could We Talk About? aims to denounce a much larger narrative: the violence resulting from drug trafficking in Mexico. Although the cultivation and export of drugs— marijuana, cocaine, and heroin—had already been in effect throughout Mexico for several decades prior to the production of the artwork, What Else Could We Talk About? responded to a current social crisis.12 After all, the Mexican Drug War, which can be defined as the Mexican government’s war against the various drug cartels operating around the country, had only begun a few years prior. Through her contribution at the Venice Biennale of 2009, Margolles brought the lives claimed by this deadly conflict to the center stage of the European art world in an effort to generate global attention to an issue which, up to that point, had been ignored by the international scene.13 Yet, in her showcasing of the social impact of the Mexican Drug War to the world, the artist stresses that she is but a mere transmitter of the tragedies continuously occurring in Mexico.14 Needless the say, Margolles’ orchestration of an artwork displaying the biological waste of murder victims in an Italian palace marks her use of shock strategy. While it is easy for one to criticize the artist’s treatment of death and her exhibition of unnamed remains as unethical, What Else Could We Talk About? embodies the transgressive artistic avenue taken by Margolles through her tangible, distressing display of death, which is at the heart of her critique of the necro-politics operating in contemporary Mexico.

To conclude, Kahlo’s The Dream and Margolles’ What Else Could We Talk About? showcase the artists’ transgressive uses of the theme of death. Whether through the illumination of an inner narrative or the denunciation of Mexico’s history of drug-related violence, these artists use the surreal idea of death to enlighten painful realities. When reflecting back on surrealism and its reductive perspective of Mexican female artists, it is captivating to contemplate the ways in which Kahlo and Margolles have both employed their artistry to carve their own paths within history, solidifying their status as renowned artists in a world that continues to undermine women’s achievements.

Endnotes

1. Nuria Carton De Grammont, “Women Artists and the Surrealist Movement,” ARTH398: 100 Years of Mexican Art, class lecture at Concordia University, Montreal, QC, presented September 26, 2023.

2. See Dream Caused by the Flight of a Bee Around a Pomegranate a Second Before Awakening, produced by Salvador Dalí in 1944.

3. Tere Arqc, “In the Land of Convulsive Beauty,” in Wonderland: The Surrealist Adventures of Women Artists in Mexico and the United States, eds. Ilene Susan Fort, Tere Arqc and Terry Geis (New York: Prestel, 2012), 67.

4. Ibid.

5. Nuria Carton De Grammont, “Women Artists and the Surrealist Movement,” ARTH398: 100 Years of Mexican Art, class lecture at Concordia University, Montreal, QC, presented September 26, 2023.

6. Arqc, “In the Land of Convulsive Beauty”, 68.

7. Nuria Carton De Grammont, “Women Artists and the Surrealist Movement,” ARTH398: 100 Years of Mexican Art, class lecture at Concordia University, Montreal, QC, presented September 26, 2023.

8. Ingried Brugger, “A Small World That Becomes So Big…” in Frida Kahlo, ed. Martin-Gropius-Bau (Munich and New York: Prestel, 2010), 13.

9. Ibid.

10. Ibid., 14.

11. Nuria Carton de Grammont, “Narco-aesthetics: Drug War and Violence in Contemporary Art,” ARTH398: 100 Years of Mexican Art, class lecture at Concordia University, Montreal, QC, presented November 28, 2023.

12. Ibid.

13. Ibid.

14. Lidia Rossner and Alexander Rossner, “Teresa Margolles: ‘What Else Can We Talk About?’ (2009), 53rd Venice Biennale.” Vimeo, 2013, video, 4:19, https://vimeo.com/69195492.

Bibliography

Arqc, Tere. “In the Land of Convulsive Beauty.” In Wonderland: The Surrealist Adventures of Women Artists in Mexico and the United States, eds. Ilene Susan Fort, Tere Arqc and Terry Geis, 65-87. New York: Prestel, 2012.

Brugger, Ingried. “A Small World That Becomes So Big…” In Frida Kahlo, ed. Martin-Gropius-Bau, 12-17. Munich and New York: Prestel, 2010.

Carton De Grammont, Nuria. “Narco-aesthetics: Drug War and Violence in Contemporary Art.” ARTH398: 100 Years of Mexican Art. Class lecture at Concordia University, Montreal, November 28, 2023.

Carton De Grammont, Nuria. “Women Artists and the Surrealist Movement.” ARTH398: 100 Years of Mexican Art. Class lecture at Concordia University, Montreal, QC, September 26, 2023.

Rossner, Lidia and Alexander Rossner. “Teresa Margolles: ‘What Else Can We Talk About?’ (2009), 53rd Venice Biennale.” Vimeo. 2013. Video, 4:19. https://vimeo.com/69195492.

When examining the work of Mexican female artists, it is crucial to underline the importance of surrealism’s role in fostering Mexican female artistry, while noting its discriminatory limitations. Fathered by French writer André Breton, surrealism’s beginnings were characterized by the development of psychic automatism, an art-making method that aimed for the suppression of reason and conventional thought to make way for the ideas brought forth by the human subconscious. The surrealist concern for the subconscious is rooted in Freudian theory, according to which dreams and other manifestations of the unconscious mind consist in an essential source of revelations pertaining to the understanding of human emotions otherwise repressed.1 Pictorially, this artistic method led to the creation of dream-like, illogical imagery, where time is often suspended and unrelated figures are juxtaposed.2 Following his multiple visits to Mexico, Breton described the country as a “constellation of seduction and dreams” and a world where surrealism could flourish.3 Interestingly, it is the “primitivity” of Mexico, contained in its people, fauna, and flora, that led to his fascination with the country’s culture and art production, as well as to his perspective of the country as surrealist.4 One could argue that Breton’s infatuation with Mexico’s surrealist “primitivity” stems from a Western paternalist gaze, which inherently views the other as illogical and, therefore, as captivating. Parallelly, Breton believed Indigenous female artists like Frida Kahlo and María Izquierdo to embody the essence of surrealism; their femininely “naïve” and “untrained” minds, which grew away from the Western world and its “advancements,” represented the rawness of humanity and a purer form of expression.5 Consequently, the mid-20th century saw a growing interest in showcasing the work of Mexican female artists—especially those who somehow responded to the surrealist quest. Kahlo’s work was notably exhibited at the International Exhibition of Surrealism held in Mexico City in 1940 even though she had repeatedly stated throughout her lifetime that she did not identify as a surrealist.6 7 Following this idea, although the arena of surrealism allowed Mexican female artistry to flourish, it is undeniable that the European art world’s interest in these artists was tinted with the misogynistic and racist perspective that prevailed in the Western world. Next to the fulfillment of a Western artistic fantasy of female primitivity, it seemed like the assertive self-fashioning of Mexican female artists did not weigh much.

Formally speaking, Kahlo’s The Dream depicts a wooden canopy bed, in which the artist herself is represented, sleeping (fig. 1). She is dressed in a white garment, her head resting on two pillows while her body is covered with a large yellow blanket. A leafed plant climbs over the blanket, taking its roots under the footboard. On top of the bed, a skeleton is depicted in a position similar to Kahlo’s, although somewhat more rigid and robot-like. Their skull is also resting on two pillows, their naked body this time covered with an explosive apparatus. With their right hand, they are holding a bouquet of pastel-coloured flowers near their chest. The background of the artwork’s composition is formed by a dimensional, cloudy setting, making the bed appear as if it is floating in the sky.

At first glance, one could certainly argue that The Dream possesses a surrealist quality for it depicts a fantastical, unearthly scene. Even if one was to ignore its title, the artwork resembles a dreamscape via the representation of a bed floating in a cloudy sky, as well as the artist’s reference to sleep. Yet, a mindful understanding of Kahlo’s oeuvre and biography suggests the depiction of an inner, personal narrative that is fully rooted in reality. Despite artists like Breton categorizing Kahlo as a surrealist, there is nothing surreal about any of her works, for they are “pieces of her life.”8 The artist’s depiction of the theme of death in The Dream, marked by the representation of a skeleton, is to be understood in relation to her own life experience, which was traversed by—but surely not limited to—many traumatic events and a great presence of pain.9 Considering the physical and psychological suffering—her illnesses, disabilities, accidents, abortions, and tumultuous romantic relationship with Diego Rivera—that punctuated her life, I argue that the superposition of a skeleton over Kahlo’s body serves as the representation of death looming over her, patiently waiting to grant her damaged body its final wish.10 Moreover, the presence of two contrasting figures in the artwork, one alive and one dead, can be related to Kahlo’s interest in the concept of duality. Like the two mirrored subjects in Kahlo’s The Two Fridas (1939), the two superposed subjects in The Dream reflect the duality of the artist’s humanity, this time encapsulated within life and death. Most importantly, it is worthy to note that the artist’s depiction of the theme of death strongly differs from the depiction of similarly large existential themes within other modern art production in Mexico, making this artwork subversive in its tackling of the theme. Just a couple decades prior to Kahlo’s creation of The Dream, muralism’s three star artists—Diego Rivera, José Clemente Orozco, and David Alfaro Siqueiros—began creating their massive, state-sponsored murals depicting mega-narratives, which discussed complex themes such as class, labour, and corruption. Unlike these murals, Kahlo’s The Dream did not aim to fulfill a social purpose; the artist’s conception of death is not represented in an effort to appeal to a national mass. Rather, Kahlo’s depiction of death is meant to share a slice of her life with her viewers. Following this idea, Kahlo’s non-social treatment of death and her centering of her own life experience in The Dream—challenging a societal expectation of female selflessness—marks the transgressive nature of her work, which went against the grain of the Mexican modern art world.

Through its blend of ready-made and performance art, Margolles’ What Else Could We Talk About? is formally divergent from Kahlo’s painting of The Dream. Exhibited as the artist’s contribution for the Mexican Pavilion of the Venice Biennale of 2009, the artwork was presented in the Palazzo Rota Ivancich—a spacious, Baroque-style palace—characterized by high ceilings, marble floors, and intricately ornamented doorways. The Biennale’s visitors were invited to silently walk through a series of rooms in which large pieces of cloth were hung on the walls. The cream-coloured pieces of cloth were completely soaked in a blood-like substance, forming dry, irregular stains (fig. 2). In each room, a person could be seen cleaning the floor with a mop (fig. 3).

It was only after viewing the artwork that the Biennale’s visitors were told the blood soaked into these pieces of cloth was real. In fact, these very pieces of cloth had previously served to clean the puddles of biological waste left by the corpses of victims of drug trafficking in the streets of Mexico’s urban agglomerations. The individuals mopping the marbled floors of the palace were members of the victims’ families, whom Margolles had invited to perform as a part of the artwork.11 Consequently, What Else Could We Talk About? builds a direct bridge between death and the viewer through the presentation of ready-made objects that were in direct contact with the bodily secretions of murdered individuals and the presence of those who mourn them, offering a tangible manifestation of the violence to which countless Mexicans have succumbed. In other words, the artwork curiously displays the use of death as a medium. Unlike Kahlo’s introspective exploration in The Dream, the use of the theme of death in Margolles’ What Else Could We Talk About? aims to denounce a much larger narrative: the violence resulting from drug trafficking in Mexico. Although the cultivation and export of drugs— marijuana, cocaine, and heroin—had already been in effect throughout Mexico for several decades prior to the production of the artwork, What Else Could We Talk About? responded to a current social crisis.12 After all, the Mexican Drug War, which can be defined as the Mexican government’s war against the various drug cartels operating around the country, had only begun a few years prior. Through her contribution at the Venice Biennale of 2009, Margolles brought the lives claimed by this deadly conflict to the center stage of the European art world in an effort to generate global attention to an issue which, up to that point, had been ignored by the international scene.13 Yet, in her showcasing of the social impact of the Mexican Drug War to the world, the artist stresses that she is but a mere transmitter of the tragedies continuously occurring in Mexico.14 Needless the say, Margolles’ orchestration of an artwork displaying the biological waste of murder victims in an Italian palace marks her use of shock strategy. While it is easy for one to criticize the artist’s treatment of death and her exhibition of unnamed remains as unethical, What Else Could We Talk About? embodies the transgressive artistic avenue taken by Margolles through her tangible, distressing display of death, which is at the heart of her critique of the necro-politics operating in contemporary Mexico.

To conclude, Kahlo’s The Dream and Margolles’ What Else Could We Talk About? showcase the artists’ transgressive uses of the theme of death. Whether through the illumination of an inner narrative or the denunciation of Mexico’s history of drug-related violence, these artists use the surreal idea of death to enlighten painful realities. When reflecting back on surrealism and its reductive perspective of Mexican female artists, it is captivating to contemplate the ways in which Kahlo and Margolles have both employed their artistry to carve their own paths within history, solidifying their status as renowned artists in a world that continues to undermine women’s achievements.

Endnotes

1. Nuria Carton De Grammont, “Women Artists and the Surrealist Movement,” ARTH398: 100 Years of Mexican Art, class lecture at Concordia University, Montreal, QC, presented September 26, 2023.

2. See Dream Caused by the Flight of a Bee Around a Pomegranate a Second Before Awakening, produced by Salvador Dalí in 1944.

3. Tere Arqc, “In the Land of Convulsive Beauty,” in Wonderland: The Surrealist Adventures of Women Artists in Mexico and the United States, eds. Ilene Susan Fort, Tere Arqc and Terry Geis (New York: Prestel, 2012), 67.

4. Ibid.

5. Nuria Carton De Grammont, “Women Artists and the Surrealist Movement,” ARTH398: 100 Years of Mexican Art, class lecture at Concordia University, Montreal, QC, presented September 26, 2023.

6. Arqc, “In the Land of Convulsive Beauty”, 68.

7. Nuria Carton De Grammont, “Women Artists and the Surrealist Movement,” ARTH398: 100 Years of Mexican Art, class lecture at Concordia University, Montreal, QC, presented September 26, 2023.

8. Ingried Brugger, “A Small World That Becomes So Big…” in Frida Kahlo, ed. Martin-Gropius-Bau (Munich and New York: Prestel, 2010), 13.

9. Ibid.

10. Ibid., 14.

11. Nuria Carton de Grammont, “Narco-aesthetics: Drug War and Violence in Contemporary Art,” ARTH398: 100 Years of Mexican Art, class lecture at Concordia University, Montreal, QC, presented November 28, 2023.

12. Ibid.

13. Ibid.

14. Lidia Rossner and Alexander Rossner, “Teresa Margolles: ‘What Else Can We Talk About?’ (2009), 53rd Venice Biennale.” Vimeo, 2013, video, 4:19, https://vimeo.com/69195492.

Bibliography

Arqc, Tere. “In the Land of Convulsive Beauty.” In Wonderland: The Surrealist Adventures of Women Artists in Mexico and the United States, eds. Ilene Susan Fort, Tere Arqc and Terry Geis, 65-87. New York: Prestel, 2012.

Brugger, Ingried. “A Small World That Becomes So Big…” In Frida Kahlo, ed. Martin-Gropius-Bau, 12-17. Munich and New York: Prestel, 2010.

Carton De Grammont, Nuria. “Narco-aesthetics: Drug War and Violence in Contemporary Art.” ARTH398: 100 Years of Mexican Art. Class lecture at Concordia University, Montreal, November 28, 2023.

Carton De Grammont, Nuria. “Women Artists and the Surrealist Movement.” ARTH398: 100 Years of Mexican Art. Class lecture at Concordia University, Montreal, QC, September 26, 2023.

Rossner, Lidia and Alexander Rossner. “Teresa Margolles: ‘What Else Can We Talk About?’ (2009), 53rd Venice Biennale.” Vimeo. 2013. Video, 4:19. https://vimeo.com/69195492.