Interwar Anxieties Through Female Representations, Between Paris and Mexico – Alice Pessoa de Barros

MAY 5, 2021

The interwar period saw many social and political changes in Europe and Latin America. Europe suffered countless deaths during World War I, women were increasingly present in the workforce, and Paris, as the center of the art world, became home to numerous foreign artists. These changes brought anxieties with regards to depopulation and xenophobia, as this new influx of foreign artists was well-received, but not without compromises1.

Interestingly, representations of women by male artists during the interwar period reflect the anxieties of that time regarding women’s increasing freedom and the presence of international artists in Paris. On the one hand, there seemed to be a tendency to return to traditional roles in France and Latin America in the 1920s which impacted the representation of women by male artists. Maternity by José Clemente Orozco and Mother and Child by Pablo Picasso are good examples of two works that visibly promote a more traditional representation of the female body as well as maternity. On another hand, xenophobic anxieties in France during that time also led to a particular depiction of women by Latin American artists who were required to make their works easily differentiated from the work of French artists, such as in Manuel Rendon Seminario’s Elongated Nude.

In the 1920s, Mexico had just gotten out of a ten year long revolution, while France was still recovering from the First World War. Both countries returned not only to traditions concerning gender roles and ideologies, but also in terms of artistic practice. In French art, this period was marked by a “return-to-order” (“retour à l’ordre”), characterized by a new appeal for classicism2. As such, women were often represented in their “traditional” roles: as mothers, caring for children, or as classical, docile nudes. This was mostly a response to the increasing presence of women in the workforce and anxieties related to underpopulation. Women were expected to take their roles as mothers more seriously and faced an increased pressure to reproduce to compensate for the many deaths of the war.

This pro-natalist position is made quite obvious in the painting Mother and Child by Picasso (fig. 1). Although this work was made in 1921, it shows very little evidence of the influence of modernism and cubism. Indeed, the monumentality of the two figures, the mother and her child, as well as the earthy colors, speak to the influence of classicism rather than that of emerging modernist movements. The look exchanged between the mother and her child conveys the touching relationship, especially as the baby reaches for his mother’s face. The woman’s white dress could also be a religious allusion to the Virgin Mary, thus portraying the “idealized mother.” This idealization of motherhood is reinforced by the fact that the woman seems to be part of nature, thus fulfilling her “natural” role as mother: indeed, because of the color of the woman’s dress and her monumental size, her figure blends in with the background, making her one with nature. This painting can be read as a way to incite women to come back to their traditional role as mothers. For Picasso, this could have been a way for him to deal with his and many men’s anxieties relating to the decreasing birth rate, heavy depopulation and changes in gender roles.

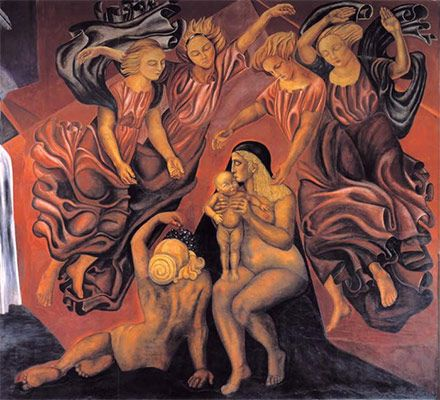

France was not the only country that saw this desire for a return to traditions. After the Mexican Revolution, some Latin American artists also attempted to cope with the same anxieties by representing women in a notable way. In José Clemente Orozco’s Maternity mural, one can find a similar response to Picasso’s regarding social changes (fig. 2). Recalling a religious nativity scene, Orozco’s mural depicts five angelic women floating in an apocalyptic atmosphere and surrounding a woman in the middle who wears a veil and holds a child.

The floating figures seem to focus solely on the mother and her child, as if to emphasize the importance of motherhood and women supporting each other in their roles as mothers. The neoclassical influence is visible in the way the bodies are represented: their elongated postures are reminiscent of classical Renaissance frescoes, almost alluding to mannerism. Finally, we are once again reminded of women’s proximity to nature and their reproductive function, as the central figure’s veil blends with the earth under her feet. The mother, although naked, could once again be identified as the Virgin Mary, the ideal mother figure, surrounded by angels, and acclaimed for giving birth.

After the first World War, Paris became the center of the art world and as a result, artists from across the globe came to the French capital to benefit from its low cost of living, government support of artists, as well as vibrant cultural life which seemed to welcome foreign influence3. In particular, the Latin American community became quite prominent. Artists such as Diego Rivera, Angel Zarraga and Manuel Ortiz de Zarrate were frequently seen in typical artistic cafés and restaurants, enjoying the Parisian lifestyle. But with this new influx of foreign artists came anxieties and apprehensions. The newly arrived artists faced increased xenophobia from the French, including art critics, who were only appeased by the marking of a clear delimitation between French and foreign art. As a result, Latin American artists who wished to be favourably reviewed by critics in order to keep their grants had to satisfy the French’s demand for “authentic” Latin American art4. For the French, that meant exotic settings, non-white subjects and primitivism, which made evident the distinction between French and foreign art.

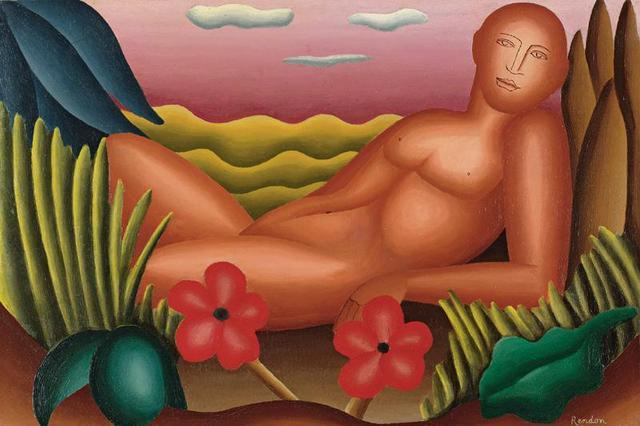

Ecuadorian artist Manuel Rendon Seminario is one of many artists that had to, at least in part, leave their desire to experiment with European modernism behind in order to produce art that would be considered “authentic” enough for French critics. This strategy is evidenced in his depiction of nude women, such as Elongated Nude from 1930 (fig. 3). The painting is quite simplistic in that the elements have few details and the figure seems flattened. This can be interpreted as a mark of the influence of cubism that the artist did not completely abandon in an attempt to reconcile it with a more “primitivist” style. However, his work also has many elements of what the French would have considered an “authentic” work: the nude woman has dark skin, the setting is definitely somewhere exotic and the colors are quite primary, mostly shades of red, green and brown. There is no trace of modern life or architecture. The female subject blends into the exotic setting, which seems to be in the middle of nowhere, far from civilization. So, although we can see some traces of experimentation with modernist features, further exploration would have made Manuel Rendon Seminario too modern or avant-garde for a non-European artist, resulting in negative critiques as well as the cancellation of his financial aid.

The representation of women within artworks gives us abundant evidence of the political and social climate of a certain period. In a time marked by anxieties concerning depopulation and xenophobia, I argue that the female subjects in the works of three foreign artists living in France act as a way of coping with this tumultuous cultural moment. In Picasso’s Mother and Child and José Clemente Orozco’s Maternity, this is visible through a conservative and traditional depiction of motherhood and femininity, while Manuel Rendon Seminario’s Elongated Nude is a response to a demand for “authentic” Latin American art.

- Michele Greet, Transatlantic Encounters (New Heaven: Yale University Press, 2018), 32.

- Greet, 23.

- Greet, 33.

- Greet, 40-41

Greet, Michele. Transatlantic Encounters: Latin American Artists in Paris between the Wars. New Haven Conn.: Yale University Press, 2018.