La Santa Muerte: A Conversation and Historical Overview by Alina Gannon

November 3rd 2025

Altar to Santa Muerte founded by Doña Quetta, Tepito, Mexico City, photo by Erin Lee

In the midst of Tepito, Mexico City stand some of the most visited shrines of La Santa Muerte.

I've heard stories about her for years now. I see her in markets, inked on people's skin, in street altars and on pendants hanging from the beautiful witches of Mexico City. Even though socially controversial and misunderstood, the cult that praises this Mexican Saint of Death grows every day. This may appear strange at first, given the fact that Mexico is predominantly Catholic and the religion already has countless Saints one could choose to venerate. Yet still, people are drawn to a figure deemed “dark” and “evil”.

But why exactly has she been so demonized by both society and the church? The devotion to the saint reflects a deeply socially unjust country. Amidst these classist, racist, sexist and homophobic realities, La Santa Muerte opens her arms and welcomes all marginalized minorities excluded from the norm of Mexican society.

I've heard stories about her for years now. I see her in markets, inked on people's skin, in street altars and on pendants hanging from the beautiful witches of Mexico City. Even though socially controversial and misunderstood, the cult that praises this Mexican Saint of Death grows every day. This may appear strange at first, given the fact that Mexico is predominantly Catholic and the religion already has countless Saints one could choose to venerate. Yet still, people are drawn to a figure deemed “dark” and “evil”.

But why exactly has she been so demonized by both society and the church? The devotion to the saint reflects a deeply socially unjust country. Amidst these classist, racist, sexist and homophobic realities, La Santa Muerte opens her arms and welcomes all marginalized minorities excluded from the norm of Mexican society.

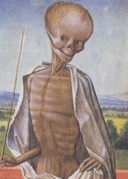

Mictlantecuhtli, seated stone figure, c. 900 CE, Museo de Antropología de Xalapa, Mexico

During the Spanish conquest starting in 1519, the inquisition prioritized an extensive annihilation and replacement of pre-hispanic spirituality with Catholicism. In fear of losing their gods to this new religion, Mexicas took attributes of Catholic saints and found ways to combine them with their own divine figures. In pre-hispanic traditions, believing in a god of death is common.

For instance, Mexicas believe in Mictlantecuhtli, a central god whose name means “the lord of the mansion of the dead.” He was created by Quetzalcóatl – a primary God to Mexicas – who sought to make humans grateful for life. The lord and his wife Mictacaicihuatl reign over Mictlán, the underworld. It might be tempting to compare this place to Hell, but it is far from it. It's not dark nor used as a torturous chamber for punishment, but rather another realm of existence. The lady of the dead, Mictacaicihuatl, shares her husband's attributes and duties, although she is known to be more flexible and embodies stereotypical feminine characteristics. She is more caring and responsible for the dead, keeping an eye over Mictlán and granting the souls of the dead the privilege of visiting the living on occasions such as El Día de los Muertos. Within Mexica cosmology, these deities were not conceived as morbid emblems of death, but as vital affirmations of life itself. They embody the duality between both states.

In Christianity, the possibility of losing eternal life makes death a taboo. If you aren't a faithful, sinless Christian, you end up in Hell and not Heaven. This makes a lot of Mexico’s population susceptible to “eternal damnation” since it's hard to remain “sinless” within their context. Mictlantecuhtli however, offers humanity a different afterlife. Hell, like Mictlán, is considered the underworld, and Satan, like Mictlantecuhtli, is the Lord of this realm. Although their stories couldn't be further apart, these few similarities – and moreover the general corpse-like depiction of Mictlantecuhtli – sparked rejection of their god from the Catholic colonizers. This made it difficult to associate the Mexica god to any Catholic Saint approved by the church. Which is why, from Mexico to Medieval Europe, the modern day iconography of the Saint is borrowed from a mix of different cultures.

During the 16th century, Europe was struck with the black plague, responsible for mass deaths which would wipe out most of the continent’s population. Christian Europeans thought of the plague as a universal punishment caused by the sinful nature of humanity. The allegorical animation of death was on the rise in the arts. Eventually making its way from Spain to Mexico during the inquisition. The iconography of Saint Death is the consequence of religious repression: the macabre skeleton figure cloaked in dark robes, with which we associate death throughout the West, was re-appropriated by Mexicas to disguise their worship of Mictlantecuhtli.

From Jean Colombe’s Book of Hours, Death Personified, 1473

Danse Macabre, fresco in Holy Trinity Church, Slovenia, 1490

La Santa is represented by a female skeleton. She wears a monk-like cloak which covers her head to toe. It's often black, but the colors can differ depending on what you want her to bring to your life: red for love, white for purity and protection, purple for health, and so on. Her devotees give her different names to make their relationship with the Saint even more personal and intimate. They also adorn her with trinkets of their own to further personalize her, clad her in different clothing, Mexican embroidery or jewelry, such as a rosary. She's almost always standing upright, holding a scale in her right hand – symbolizing the balance between life and death – or at times a globe to represent the universality of dying. In her left hand she firmly grips a scythe, which represents the split of life and death. However, as is the case with most oral based traditions, iconography and mythology can vary slightly depending on who you ask.

Some say she is the daughter of Christ, who gave her a burdensome responsibility: collecting the souls of the dead. Worried about the pain it would cause her to take away the souls, she begged Christ to at least relieve her of the pain of her senses. Without sight, scent nor vision her job would hopefully be easier, relegating her to a skeletal physical state. Contrary to popular bias, she is believed to do God’s work, not the Devil’s. She is known to be on the jealous side, to be overprotective and highly emotional. She is quick to act, fast and efficient in answering prayers. Yet she is mostly kind and caring, associated by many to a "comforting mother figure" and treated as such by her cult

The way Mexicans honor their Saints is most notably recognized during the Day of the Dead. We make altars for the people we've lost, topped with offerings designated to each one, as we do with our deities. On a day to day, La Santa Muerte likes to be spoiled with flowers, tobacco, notes and letters, even tequila. But she isn't necessarily extravagant: she will appreciate anything big or small as long as your intentions are pure and genuine. She doesn't discriminate; there are no requirements to be a part of her cult. She has no strict expectations for her followers and no reasons to condemn them, different to the Christian Church.

Photo by Erin Lee, La Santa Muerte, Mexico, 2014, Mexico, Vice News

Tepito is located in the historical center of Mexico City. It's a lively, busy, tumultuous neighborhood. Historically, Tepito was one of the last sites of resistance against Spanish colonialism. Once it was finally defeated, Hernan Cortez made sure to place extensive security around it since the area was used to expel and segregate countless Mexicas. This segregation has had persistent effects up to this day in Mexican society. The reality is, Spanish colonialism never left Mexico and its effects on Tepito are as noticeable as ever. The neighborhood (barrio) is home to the lower working class of Mexico City, for those who can’t afford the expenses and rates of the wealthier neighbourhoods. Those who can't afford an education. Those who have a hard time getting medical assistance. Those marginalized by prejudices of their skin color and denied “respectable” employment. Those born into businesses outside the law. Tepito houses working mothers who struggle to feed their kids, who can’t get legal protection against their abusive husbands, trans women who are fetishized in sex work but rejected in their day to day, and children who are forced to labour before they can even speak.

Tepito's reputation is tainted on many levels: it's considered to be dirty, uncared for, dangerous and incredibly busy. It’s hard to walk through, loud, and uncomfortable. The streets are even lined with plastic awnings that block out the sky, creating a claustrophobic sentiment. It's an infinite outdoor market where everything and nothing is possible. You can find cheap clothing, blocks and blocks of blenders, jewelry, stuffed animals, cleaning products, shoes, washing machines, pirated movies. Blocks and blocks and blocks of books and perfumes, fabrics, furs and so much more.

Mexico City is the most enchanting place in the world. But like any country, it has more problems than one could count. Poverty is intoxicating. Women are raped. Murdered. Everyday. Families are torn apart by systemic organized crime. This way of life makes it incredibly difficult to stay unconditionally faithful to a supposedly omnibenevolent God whose institution forbids your culture and traditions, who is often depicted with white skin and blue eyes, dressed in Roman drapery surrounded by gold – far from most of Mexico's reality. A God who has historically been used to outlaw homosexuality, or as a pretext to confine women into hysteria, vessels for sexual reproduction, wives, property – stripped of their full humanity.

La Santa Muerte is often associated with crime because most of her followers are victims of this perpetual systematic poverty which constricts possibility. Yet, she's a glimmer of freedom veiled by the institutional marginalization of the Catholic Church. She represents a new hope, one that hasn't been corrupted by western men, politics and binaries. She is a refreshing figure because she’s a manifestation of our ancestry overlapping with modern folklore. Despite her devotees' requests to canonize her, the Vatican declared the cult to be “blasphemous” in 2013. She was deemed a temptation of the devil to trick people into falling in love with death. On the contrary, La Santa Muerte shows the resilience and determination of the Mexican people to resist the neocolonial attempts of the Catholic Church who, like the Spanish, want to stomp out Indigenous and Mexican spiritual practices. The cult invites us to question why it is that we deem death so negatively. We all live our lives with an expiration date. Natural death in some cultures is a great achievement. In Mexica mythology, death is just as precious as life is, it is a blessing even. There’s no fear nor resentment. But through history we've been made afraid of the one thing we can never avoid. The Saint welcomes us to reconsider our relationship with death in a way that might grant us some comfort. Especially in cases where one is exposed to systematic risks and hardships. If the Catholic Church isn't welcoming for minorities and if your government won’t protect you in the face of death, where should your faith stand?

Interview: A conversation with Estela

Estela is a family friend from Mexico City that I've grown up with. For the past 15 years she has worked as a housekeeper in my best friend's home, but really she’s part of the family. I remembered she used to have a boyfriend that was devoted to La Santa. Although Este didn't used to like speaking about the cult, her feelings for the faith have changed. After a short call, this is what I learned from her:

Estela: Well, you can ask her for favors and stuff. Supposedly she doesn't “charge” for the favors she grants you because, well, at the end of the day, we are just a living image of her. Your flesh is your flesh but what are we underneath that? Obviously. We are the same. We are the same because when your flesh leaves you, well, you end up just like her, calaquita

Alina: Yes, of course.

Estela: So, it's logical. Look, if you go online right now and do some research you'll find good things and bad things. Because of course, there's people that still can't accept the reality that she's good. The same way that you see people talk bad about the Catholic Church, so. That's my… my… but I don't know. What else would you like to know? Tell me. You tell me what you want to know.

Alina: Mmmm. Well. Like, how did your ex boyfriend end up being part of the cult? Like, was it his family or…

Estela: He, well, they had this woman that did these things and she obviously was a devotee to the saint you know? That woman would have been given the gift to cure you. Like, she… Well once she told him "I don't do harm. My saint doesn't allow me to”. Like if you go and you tell her “I feel bad” such and such, it would be like the doctor. He'll tell you “oh well you're alright” then you'll know you're good. But then if you go and the doctor tells you “no you're sick” and so on then you know something is off. If you go with this woman the first thing she'll tell you is if there's something wrong with you. And you'll be like, “Why?”. And she'll tell you…“Oh well because there's this person in your home that wishes you harm, or the neighbor or friend, whatever whatever. So she takes care of that. She keeps you safe from that. Just like a doctor, she'll diagnose you. But remember that it's the Saint that works through her.

Alina: Right, right. So she’s like a medium.

Estela: Aha. Exactly.

Alina: So, did your ex go to this woman for health reasons?

Estela: Exactly. And that's where they started to believe in the Saint, because they saw that she was… mmmm how can I say this. Like, Alina, everything this woman would tell them was true.

Alina: So she would literally just know what was wrong with them and she would be right?

Estela: Exactly.

Alina: Have you ever asked her for anything?

Estela: Well, remember when I lived with him that I would go there a lot?

Mhm well, I was very honest with this woman, I said… I don't know if I ever told you this, I don't think so. But I told her “I’ll do my thing, you'll do your thing cause I don't believe in that”. Like whatever. I mean it's not like I'm pretending like I don't know anything about that. Because obviously, people tell you about their faith and stuff which is why now I know more. But like I said, it's not that I think she's bad like other people do but I also am not super into it.

Alina: And do you think the cult has been growing more and more?

Estela: Of course, because now there's more churches that allow her to be venerated. Like once I went to this Basilica with a friend and there was the market and everything, obviously the market of the Basilica. And there were a lot of devotees you know? If you go by some place that sells santitos the first thing you'll see is her. Because it's not like… it's not like before, you don't have to hide your faith anymore.

Sources

Lacunza, Michel A. Olguín, “Te presento a Mictlantecuhtli, el dios mexica de la muerte”, octubre 29, 2020, UNAM Global Revista: https://unamglobal.unam.mx/global_revista/te-presento-a-mictlantecuhtli-el-dios-mexica-de-la-muerte/

XIU, “La historia de 5 deidades prehispánicas que fueron sincretizadas con figuras católicas” Matador Network, 24 Abril 2020, Mexico: https://matadornetwork.com/es/santos-catolicos-sincretizados-con-deidades-antiguas/

Silleras-Fernandez, N. (2024). Performing death in medieval Iberia: an introduction to the end of life. Journal of Medieval Iberian Studies, 16(1), 1–14. https://doi.org/10.1080/17546559.2023.2296993

“Region at the corner of Bliss and Nirvana, Politics, Identity and Faith in New Migrant Communities”, Lorentzen, Lois Ann “Devotional Crossings: Transgender sex workers, Santísima Muerte, and Spiritual Solidarity in Guadalajara and San Francisco”, Duke University Press, 2009, Durham and London.

A. Calvo-Quiros, William, “Undocumented Saints: The Politics of Migrating Devotions. La Santa Muerte: the patrona of the Death-Worlds”, 2022, Oxford University Press, New York, United States of America

Osegueda, Rodrigo, “Tepito, historia del barrio bravo más icónico de México”, Mexico Desconocido, Ciudad de Mexico: https://www.mexicodesconocido.com.mx/tepito.html

“El Vaticano considera “blasfemia” la Santa Muerte”, BBC News Mundo, 9 mayo 2013 https://www.bbc.com/mundo/ultimas_noticias/2013/05/130507_ultnot_vaticano_santa_muerte_mexico_cch#:~:text=El%20cardenal%20Gianfranco%20Ravasi%2C%20secretario,a%20venerar%20la%20figura%20esquel%C3%A9tica.