“My Face for the World to See”: Representing Candy Darling – Sarah Hollyer-Carney

FEBRUARY 17, 2020

Cw: sexual assault, transphobia

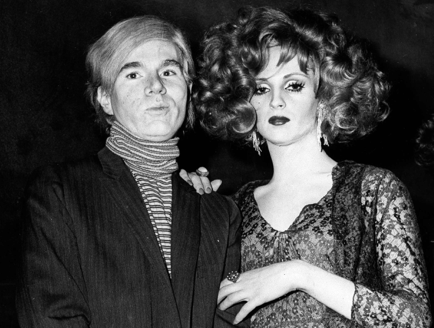

Candy Darling is almost always spoken about in relation to well-known male artists. As an actress, model and muse working in New York City’s downtown arts scene in the 1960s and 70s, Darling starred in one of Tennessee Williams’ final plays, and was depicted on her deathbed by photographer Peter Hujar. She is the subject of The Velvet Underground’s “Candy Says,” as well as one of the subjects of Lou Reed’s “Walk on the Wild Side.” But it is for her role as one of Andy Warhol’s “superstars” that she is primarily remembered today.

Darling grew up in Long Island, watching the growing queer trans community in New York from a distance. She was relentlessly bullied in high school for her gender expression, which culminated in her attempted murder and subsequent drop out. Darling idolized the glamorous femininity of old Hollywood movie stars such as Kim Novak, Rita Hayworth and Lana Turner throughout her childhood, and she eventually left home for the city in order to transition and become a movie star herself. In the 2010 documentary Beautiful Darling, George Abagnalo, one of Darling’s co-stars in Women in Revolt, says that “to be considered a beautiful woman –– a beautiful movie star –– was the most important thing in Candy’s life.” Darling’s connection with Andy Warhol and her appearances in his films did a great deal to help her achieve that dream. In the small world of Warhol’s Factory scene, she was able to become the kind of movie star she had always longed to be. Darling remains among the most well-known historical trans people today.

Warhol and Darling were interviewed together before the premiere of the film that would eventually become Women in Revolt. As Darling describes the film, an interviewer narrates –– over her –– that “Candy is a man.” Despite this, the narrator admits, “in Warhol’s phrase, she is a real lady.” The interviewer considers Darling’s legitimacy as a “real lady” to be entirely contingent on how Warhol perceives her. And in a sense, he is correct; Darling’s appearances in Warhol’s films gave her fame, but it also brought her significantly wider acceptance as a woman. Critics writing about Darling would frequently compare her to her primary idols, glamorous movie stars like Kim Novak. Warhol’s films gave Darling the stage upon which she could enter into this cultural role, at a time when there was essentially no precedent for a trans woman to do so.

But none of this changes the manner in which Warhol depicted Darling. Though he did not direct his films, he was the producer, and he would have most likely been responsible for casting and creating the roles she played. Warhol’s anti-feminist satire Women in Revolt features Darling, along with Jackie Curtis and Holly Woodlawn –– two other trans Warhol superstars –– as radical feminists. The film’s main characters are misogynistic caricatures of feminists in the 1970s women’s liberation movement. They are based on Warhol’s perception of extremist figures like Valerie Solanas. The decision to cast trans women to play these radical feminists is its own provocation, as transphobic rhetoric characterized much of second-wave feminism. Germaine Greer’s book The Female Eunuch, published a year before Women in Revolt was released, is a popular trans-exclusionary radical feminist text. In a 1989 interview with Independent Magazine, Greer describes an encounter with a trans woman to whom she refers as “it.” She describes the trans woman’s face, which was “thickly coated with pancake make-up through which the stubble was already burgeoning,” and she mocks her “enormous, knuckly, hairy, be-ringed paw.” For Warhol to play on this bigotry by casting trans women, whose supposedly regressive gender performance outraged transphobic feminists is –– perhaps unintentionally –– subversive. Women in Revolt is hardly a revolutionary film, but this indicates that Darling’s involvement in the project was not a matter of promoting Warhol’s ideology.

In Women in Revolt, Warhol’s contempt for the women is palpable: five minutes into the film, Holly Woodlawn’s character semi-coherently rants about feminist principles. Then, she is choked, slapped, and raped by her boyfriend. Darling is beaten and sexually assaulted in the film’s concluding scene as well. In Women in Revolt and in Warhol’s other projects, trans women are depicted solely as victims of male violence. What kind of femininity, then, did Candy Darling have the opportunity to achieve? Warhol gave her a platform where she could become a glamorous icon, but he also maintained the authority to define what kind of woman she would be in the public imagination. As Darling recounts the plot in the Women in Revolt interview, she adds that “at the end of the film I’m murdered, I think.” Warhol corrects her, dryly: “no, raped.”

“I call myself Candy Warhol now,” Darling jokes in the Women in Revolt interview. “I’m cashing in.” Despite the fame that came along with Warhol’s films, Darling lived in poverty for most of her life. She could not afford housing, and she regularly went hungry, even after the films had been released. Warhol is often praised for being “generous” with his acceptance of cultural outsiders. The narrator of the Women in Revolt interview claims that “Warhol is the salvation of his superstars” over an image of Warhol in a Christ-like position, and that Warhol “almost died, so that [his stars] might almost live.” But Warhol famously paid his actors very little, claiming that exposure and access to the Factory were compensation enough. Darling’s case is particularly striking, because she was more than just an actor to Warhol. She was one of the most significant muses to Warhol’s collaborators and friends, and was a widely admired figure in the downtown arts scene. She would regularly appear with Warhol at events and in interviews. Darling leant Warhol and his associates a form of underground credibility: he was able to benefit from his association with Darling in social capital, the accumulation of which was arguably the main goal of his career. Darling lived the life of the “street queen:” glamorous and impoverished, and she embodied the type of “authenticity” that Warhol has been accused of lacking. Warhol exploited her transness –– and her uniqueness –– to make himself appear more interesting. While Darling would also gain social capital from her appearances with Warhol, the admiration she received from artists did not help her make ends meet; admiration only means so much when one cannot afford to eat. At the time of his death, Andy Warhol’s net worth was $220 million.

Darling is often remembered as a tragic figure, but she was known during her life for possessing a profound optimism and wonder towards femininity and the world around her. As artist Greer Lankton observes, speaking about Darling’s personal diaries in an interview at the 1995 Whitney Biennial: “all [Darling] talks about is her makeup.” Darling’s writings confirm this; she almost never discusses her traumatic childhood, nor her poverty, nor her experience with dysphoria, nor the weight of the intolerance she experienced as a trans woman. Instead, Darling writes about what makes her happy. She refers to her mother’s modest house in Long Island as her “country home” –– she would frequently use expressions like this. Darling’s mother did not approve of her daughter’s feminine gender expression at first. She was later quoted as saying that upon seeing Darling standing before her one day as a woman, she simply could not argue anymore. Her daughter was “just too beautiful and talented.” Darling had never witnessed a trans woman achieve the type of glamorous fame that she desired, yet she still believed that she would succeed. Darling’s optimism has made her performances compelling, and has allowed her to become a significant figure in popular culture.

Candy Darling died at the age of 29 from leukemia. She has become an iconic figure in trans history in the decades since. On her deathbed, Darling wrote a letter explaining that she had fallen into a deep depression in the months leading up to her illness, and said that she believed the depression had actually caused her leukemia. She died surrounded by her friends and admirers. At the end of her letter, Darling writes: “Before my death I had no desire left for life…did you know I couldn’t last? I always knew it. I wish I could meet you all again.”