Undomesticated: How Shadi Ghadirian’s Photography Humorously Challenges Iranian Society’s Domestication of Women by Yasmine Nowroozi

November 05, 2024

In both Western media and the Islamic regime, Iranian women remain defined by the role they serve in the state: second to men and confined to the domestic sphere. Iranian women are stripped of their sense of self and are, instead, given the role of wife as their sole purpose within society. This lack of autonomy also extends to their bodies as Iranian women must adhere to the wearing of a state-mandated veil. Though the Islamic regime forbids its residents to voice their discontent, many Iranian women have brazenly defied the government and have begun expressing their concerns through creative means. Art has become the preferred outlet for many Iranian women when criticising the Islamic regime. Namely, critically acclaimed Iranian photographer Shadi Ghadirian challenges the Iranian government’s forced female identity in her series, Like Every Day, wherein Ghadirian humorously confronts the role of the Iranian woman as a domestic.

Her Body, Their Choice

Shortly after the fall of the Shah of Iran in 1979, the Islamic regime quickly rises to power, hampering all of the gender equality advancements made during the Shah’s reign (Shahandeh). Under Islamic rule, women, with a particular emphasis on the female body, become the canvas onto which the state projects its desired image of the ideal domestic woman and religious policies (Shahandeh). Katy Shahandeh highlights Shiism’s concern with the female body, saying that “in Shiite orthodoxy, the female body has always been a contested site whereupon the battle for male supremacy has been fought, and a man’s honour is closely tied to a woman's body”. Thus, religious men in power do not view the female body as being the physical flesh of a woman but rather as merely a source onto which a man can exert dominance and force. Aside from policies, the regime’s desire to possess and constrain the female body also manifests through its gendering of spaces, with the public sphere owned by men (Shahandeh). Female segregation within the public domain is due to the government’s belief that the modernisation of their women causes the decline of “Islamic values, cultural denigration, and the weakening of the family” (Moghadam 2). In other words, the modern Iranian woman of the 1960s has strayed too far from her intended roles as mother and housekeeper (Moghadam 2). By enforcing the compulsory veil and limiting women’s participation in public domains, the Iranian government reinstates these female gender roles in Iranian society (Moghadam 2). The veiled and segregated woman has come to symbolise “the moral and cultural transformation of society” (Moghadam 2).

An example of this sense of control and gendering of spaces lies within the state’s regulation of art. Art, during the early years of the Islamic regime’s rule, is repressed and is meant to reflect the regime’s beliefs (Shahandeh). Values expressed in the Islamic regime’s ideological campaign include denigration of the West, female modesty, and her caretaker role within the family (Moghadam 2). Thus, the imagery produced during this period promotes the regime’s Islamic ideologies and involves women engaged in what the state deems socially and ethically appropriate behaviours, such as being veiled. Images that do not conform to nor reflect the regime’s ethos are deemed inappropriate (Shahandeh). To further prevent the risk of inappropriate art, the government resorts to closing most of the country’s art galleries which deprives Iranian women from producing art publicly and, therefore, compels them to reclaim their space in the private sphere (Shahandeh).

Though censorship and the presence of morality police throughout the streets of Iran obligate women to adhere to religious rule in public, many dare to defy the regime and communicate their grievances through creative means (Shahandeh). Iranian female artists, like Shadi Ghadirian, are and remain pillars of the feminist movement within Iran. Shahandeh underscores the importance of art for the feminist movement in the following:

Contemporary Iranian women artists have, in this manner, been at the forefront of new artistic developments and have parlayed their existential angst visually, finding new creative strategies to critique the socio-political status quo and question the underlying structures, to instead weave their own alternative narratives. This has engendered an art which expresses doubt, uncertainty and ambiguity regarding knowledge and crisis of identity, which is both personal and cultural.

Traditionally, Islamic law states that those who appear in public without the appropriate covering may be subject to an Islamic penalty, meaning seventy-four lashes to the body (Mir-Hosseini 7). The harshness of this enforced policy has let the veil come to symbolise religious indoctrination and female oppression. That said, inclusion of the veil within a work is imperative, for it not only denotes the female presence but is also mandatory according to censorship laws. Should the subject of the image in question be a woman, the artist will not be permitted to exhibit their piece without including the veil (Shahandeh). One may interpret the inclusion of the chador into a piece of art as the artist's challenge to public morality laws and state-mandated identity and uniformity. Within these works of art, women are no longer subservient housewives clad in shapeless fabric but rather audacious individuals who want to reclaim their space despite the political risk it may pose. Hence, over the last four decades, art has remained an expressive outlet for the socio-political concerns of many Iranian women artists. The veil will remain emblematic in various works, such as by Iranian photographer Shadi Ghadirian.

The Domestic Woman Re-Imagined

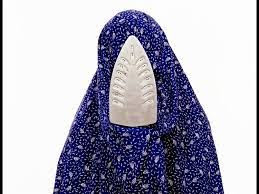

Iranian female artist, Shadi Ghadirian, continues to fashion her creative works around the socio-political changes enforced by the Islamic Regime as a means of covertly expressing her discontent. This newfound sense of female voice and identity is shaped through Ghadirian’s use of imagery imbued with metaphor and allegory. The obscurity behind the message of these works grants Gharidian a sense of invisibility from the prying eyes of the oppressive regime (Shahandeh). As previously discussed in the aforementioned paragraph, the image of the veil is of great significance within Iranian society and art, but Ghadirian’s reconceptualization of the state-mandated veil, chador, challenges its socio-political significance (Shahandeh). Though its original purpose serves as a covering of the female body and identity, the veil takes on a new life within her work. Ghadirian’s portrait series, Like Every Day, defies this concept of the veiled, domesticated woman through her use of metaphor and humour; she presents a collection of faceless figures cloaked in various coloured chadors. In place of faces, Ghadirian has humorously substituted them for an assorted mix of household items, such as a grater (fig. 1), an iron (fig. 2), and a broom (fig. 3). Although the figures remain anonymous, the viewer grasps their female gender through the chador, a veil worn by women, and the domestic items, an activity stereotypically associated with women (Shahandeh). These domestic items within these photos belong to Ghadirian as they have been gifted to her following her wedding (Saatchi Gallery). In fact, in an interview regarding the nature of this series, Ghadirian shares that “marriage shows me how a large segment of women in our society are bound by these objects; I want to know how Iranian women go through life with these items, and how things are different for women from other countries” (Stamps 32). Thus, Ghadirian’s choice of objects reflects Iranian society’s traditional sexist beliefs and their desire to have women conform to these beliefs. Ghadirian places each faceless figure behind a simple white backdrop, thus intensifying the viewer’s gaze on the two elements within the images: the household item and the chador. The absence of discernible identity within these portraits hints at the idea of a “state-imposed identity that attempts to efface individual identity” (Shahandeh). In other words, the portraits criticise the Iranian government’s attempts to strip its women of a sense of self and forcing an identity onto them entrenched in gender stereotypes.

In conclusion, Iranian women artists translate their distaste for their socio-political situation into their art. An example of this lies within the photographer work of Shadi Ghadirian. Her series, Like Every Day, challenges Iranian society’s prescribed role of Iranian women through her use of both the chador and domestic items, satirising the Iranian government’s reduction of the female identity to a product of male needs.

Iconography

![Fig. 1 Untitled in Like Every Day series by Shadi Ghadirian, 2000.]()

Her Body, Their Choice

Shortly after the fall of the Shah of Iran in 1979, the Islamic regime quickly rises to power, hampering all of the gender equality advancements made during the Shah’s reign (Shahandeh). Under Islamic rule, women, with a particular emphasis on the female body, become the canvas onto which the state projects its desired image of the ideal domestic woman and religious policies (Shahandeh). Katy Shahandeh highlights Shiism’s concern with the female body, saying that “in Shiite orthodoxy, the female body has always been a contested site whereupon the battle for male supremacy has been fought, and a man’s honour is closely tied to a woman's body”. Thus, religious men in power do not view the female body as being the physical flesh of a woman but rather as merely a source onto which a man can exert dominance and force. Aside from policies, the regime’s desire to possess and constrain the female body also manifests through its gendering of spaces, with the public sphere owned by men (Shahandeh). Female segregation within the public domain is due to the government’s belief that the modernisation of their women causes the decline of “Islamic values, cultural denigration, and the weakening of the family” (Moghadam 2). In other words, the modern Iranian woman of the 1960s has strayed too far from her intended roles as mother and housekeeper (Moghadam 2). By enforcing the compulsory veil and limiting women’s participation in public domains, the Iranian government reinstates these female gender roles in Iranian society (Moghadam 2). The veiled and segregated woman has come to symbolise “the moral and cultural transformation of society” (Moghadam 2).

An example of this sense of control and gendering of spaces lies within the state’s regulation of art. Art, during the early years of the Islamic regime’s rule, is repressed and is meant to reflect the regime’s beliefs (Shahandeh). Values expressed in the Islamic regime’s ideological campaign include denigration of the West, female modesty, and her caretaker role within the family (Moghadam 2). Thus, the imagery produced during this period promotes the regime’s Islamic ideologies and involves women engaged in what the state deems socially and ethically appropriate behaviours, such as being veiled. Images that do not conform to nor reflect the regime’s ethos are deemed inappropriate (Shahandeh). To further prevent the risk of inappropriate art, the government resorts to closing most of the country’s art galleries which deprives Iranian women from producing art publicly and, therefore, compels them to reclaim their space in the private sphere (Shahandeh).

Though censorship and the presence of morality police throughout the streets of Iran obligate women to adhere to religious rule in public, many dare to defy the regime and communicate their grievances through creative means (Shahandeh). Iranian female artists, like Shadi Ghadirian, are and remain pillars of the feminist movement within Iran. Shahandeh underscores the importance of art for the feminist movement in the following:

Contemporary Iranian women artists have, in this manner, been at the forefront of new artistic developments and have parlayed their existential angst visually, finding new creative strategies to critique the socio-political status quo and question the underlying structures, to instead weave their own alternative narratives. This has engendered an art which expresses doubt, uncertainty and ambiguity regarding knowledge and crisis of identity, which is both personal and cultural.

Traditionally, Islamic law states that those who appear in public without the appropriate covering may be subject to an Islamic penalty, meaning seventy-four lashes to the body (Mir-Hosseini 7). The harshness of this enforced policy has let the veil come to symbolise religious indoctrination and female oppression. That said, inclusion of the veil within a work is imperative, for it not only denotes the female presence but is also mandatory according to censorship laws. Should the subject of the image in question be a woman, the artist will not be permitted to exhibit their piece without including the veil (Shahandeh). One may interpret the inclusion of the chador into a piece of art as the artist's challenge to public morality laws and state-mandated identity and uniformity. Within these works of art, women are no longer subservient housewives clad in shapeless fabric but rather audacious individuals who want to reclaim their space despite the political risk it may pose. Hence, over the last four decades, art has remained an expressive outlet for the socio-political concerns of many Iranian women artists. The veil will remain emblematic in various works, such as by Iranian photographer Shadi Ghadirian.

The Domestic Woman Re-Imagined

Iranian female artist, Shadi Ghadirian, continues to fashion her creative works around the socio-political changes enforced by the Islamic Regime as a means of covertly expressing her discontent. This newfound sense of female voice and identity is shaped through Ghadirian’s use of imagery imbued with metaphor and allegory. The obscurity behind the message of these works grants Gharidian a sense of invisibility from the prying eyes of the oppressive regime (Shahandeh). As previously discussed in the aforementioned paragraph, the image of the veil is of great significance within Iranian society and art, but Ghadirian’s reconceptualization of the state-mandated veil, chador, challenges its socio-political significance (Shahandeh). Though its original purpose serves as a covering of the female body and identity, the veil takes on a new life within her work. Ghadirian’s portrait series, Like Every Day, defies this concept of the veiled, domesticated woman through her use of metaphor and humour; she presents a collection of faceless figures cloaked in various coloured chadors. In place of faces, Ghadirian has humorously substituted them for an assorted mix of household items, such as a grater (fig. 1), an iron (fig. 2), and a broom (fig. 3). Although the figures remain anonymous, the viewer grasps their female gender through the chador, a veil worn by women, and the domestic items, an activity stereotypically associated with women (Shahandeh). These domestic items within these photos belong to Ghadirian as they have been gifted to her following her wedding (Saatchi Gallery). In fact, in an interview regarding the nature of this series, Ghadirian shares that “marriage shows me how a large segment of women in our society are bound by these objects; I want to know how Iranian women go through life with these items, and how things are different for women from other countries” (Stamps 32). Thus, Ghadirian’s choice of objects reflects Iranian society’s traditional sexist beliefs and their desire to have women conform to these beliefs. Ghadirian places each faceless figure behind a simple white backdrop, thus intensifying the viewer’s gaze on the two elements within the images: the household item and the chador. The absence of discernible identity within these portraits hints at the idea of a “state-imposed identity that attempts to efface individual identity” (Shahandeh). In other words, the portraits criticise the Iranian government’s attempts to strip its women of a sense of self and forcing an identity onto them entrenched in gender stereotypes.

In conclusion, Iranian women artists translate their distaste for their socio-political situation into their art. An example of this lies within the photographer work of Shadi Ghadirian. Her series, Like Every Day, challenges Iranian society’s prescribed role of Iranian women through her use of both the chador and domestic items, satirising the Iranian government’s reduction of the female identity to a product of male needs.

Iconography

Works Cited

Mir-Hosseini, Ziba. “The Politics and Hermeneutics of the Hijab in Iran: From Confinement to Choice”. The Muslim World Journal of Human Rights, vol. 4, no.1 (2007), p.7

Moghadam, Valentine. “Women in the Islamic Republic of Iran: Legal Status, Social Positions, and Collective”.

Shahandeh, Katy. “Deconstructing Feminist Strategies by Contemporary Iranian Women Artists”. Curating as Feminist Organizing, edited by Elke Krasny and Larry Perry, Routledge, 2003.

Stamps, Samantha. “Culture, Identity, and Modernity in Iranian photography”. Mcnair Scholars Journal, vol. 17, no. 1 (2013), pp. 32.